So you want to be an entertainment lawyer? Relationships are essential, says Eminem attorney Howard Hertz

"Are you being accused of murder?" the normally serious attorney asked, only half-joking. "Because if so, I'm your guy."

The then 20-something Wayne State Law School graduate was a public defender, working murders, when the husband of one of his wife's friends needed a lawyer to review a contract he was signing.

Like most artists, the young man had little interest in legalese — he just wanted to make music and was prepared to sign whatever the record label put in front of him.

Howard Hertz reluctantly agreed to take the case, after explaining it wasn't his speciality. The client gave him a book on entertainment law to help him brush up, and Hertz proved a quick study.Â

Understanding the law is fine, and most attorneys could do it, but understanding one's options as a negotiator is another matter. After renegotiating the contract to include several clauses — the best of which was a reversion of copyright from label to artist if his work wasn't used in an agreed-upon timeframe — Hertz put the matter to bed.

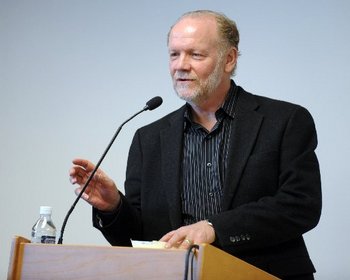

Entertainment lawyer Howard Hertz speaks to a group of budding entertainment law school students at Cooley Law School in Ann Arbor on Tuesday evening. Lon Horwedel | AnnArbor.com

But then the phone kept ringing with requests for Hertz to look over this contract, renegotiate that clause, take on this client. It became clear to Hertz that entertainment, and not public defense, was his calling.Â

It was the late 1970s, years after Motown had left Detroit, and decades before Hollywood would be lured to the north coast by film incentives. Hertz became a respected name in the industry and soon found himself representing clients like George "P Funk" Clinton, Elmore Leonard, Atlantic Records and, since 1995, the biggest name of them all —Â Marshall Mathers III, better known as Eminem.

Hertz is part-lawyer, part-agent, and always an advocate. The lifelong music fan handles contract negotiations, helps clients form legal entities to protect their assets and even manages a few acts.

Hertz's firm, Hertz Schram PC, has some 30 lawyers in a range of practices from criminal defense to bankruptcies to personal injury suits. Though Hertz put food on the table in the early years after law school by working murders, today when a client faces criminal charges — as Eminem did on a number of gun-related matters in the early part of the last decade — Hertz's partner, Walter Piszczatowski, a former federal prosecutor, steps in.

Relationships are essential to any lawyer, Hertz explained to two-dozen students at the Ann Arbor branch of the Thomas M. Cooley Law School on Tuesday. And that's especially true of entertainment lawyers working in outposts like Michigan, which is home to plenty of talent but not as much homegrown industry.

On more than one occasion, one of Hertz's clients has been urged to go with a New York-based lawyer but decided to stay with Hertz instead.

That's why it's possible for him to work full-time as an entertainment lawyer out of Bloomfield Hills, removed as it is from both the New York recording industry and the Hollywood film industry.

Karen Poole, career development coordinator for the Ann Arbor campus of the Thomas M. Cooley Law School, arranged the lecture. She brings attorneys like Hertz to campus every week in fields as disparate as criminal, sports, entertainment and intellectual property law to supplement what students learn in the classroom.

Charles Boike, president of the Entertainment Law Society at Cooley, sounded like a younger Howard Hertz as he outlined his vision as an entertainment lawyer for AnnArbor.com in the minutes before Hertz took the podium.

"The way I look at it is: Artists want to create. But they need someone to protect their legal interests — copyrights, negotiations, formng their own businesses, everything."Â

A graffiti artist and a music lover when he's not studying the law, Boike described most artists as having the same mentality as Hertz's first client, willing to sign whatever record labels put in front of them.

"Let's just say I plan to aggressively represent my clients," said Boike, a second-year law student at Cooley. "I will be the bulldog so they can focus on being creative."

But in a lot of ways the path is clearer for Boike than it was for Hertz, all those years ago. There were no film incentives back then, and though Hertz characterized Gov. Rick Snyder’s plan to cap Michigan’s nation-leading film incentives as “a killer” of the upstart local film industry, this is a better time to be in the entertainment business than the late '70s.

“There are a lot of lawyers in Michigan who do entertainment law but they’re also chasing ambulances while they do it,” Boike said, adding that Hertz was impressive not only for his client list but for the fact that he gets to work in his passion full-time.

Much like musicians often hope to book enough gigs that they don't have to work as baristas or bartenders, a number of the law students at Hertz's lecture held up a full-time entertainment law practice as a professional goal.

Then, as now, Hertz said, the key is relationships and experience. Networking is crucial in the early phases; most people will go with names they know or names referred by people they trust. Reputation is essential. Satisfied clients and the word-of-mouth buzz they create are often the most effective form of advertising.

While Hertz didn't even know that the field existed and was given his first book on entertainment law by a client, the 20- and 30-somethings at Tuesday afternoon's event are well aware of the opportunities around them.

Their challenge is finding enough work, locally, to continue building the skills and the reputation that will bring in more business. Snyder's 2011 budget proposal, which includes a $25 million cap on Michigan's nation-leading film incentive program, was discussed as a threat to the budding local film industry, an industry Hertz once described as having "billion-dollar" potential. But even with the cap, Michigan would still attract more film-related business to Michigan than there was before the incentives. That translates into plenty of work for the lawyers industrious enough to build relationships with the industry and strong reputations locally.

Jinan Hamood is in her first term at Cooley Law, still slogging through the core curriculum. The University of Michigan graduate hopes to practice sports law someday and said Hertz's lecture was encouraging in showing it could be done locally.

"There aren't many attorneys in Michigan who can make a living off of entertainment law," she said. "It was just good hearing that it's even possible to do in this area, without running off to the East or West Coast."

Today, Hertz dedicates all of his time to entertainment-related interests. He also teaches entertainment law courses at the University of Michigan and Wayne State law schools. He said he was also offered a similar opportunity at Cooley Law School but just doesn't have time to teach anything more than the occasional seminar.

James David Dickson can be reached at JamesDickson@AnnArbor.com.