The Roller Coaster Chronicles: Supply room therapy

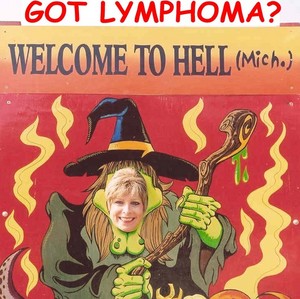

Nothing could have stated how I felt any better than this. | photo by Alex de Parry

Readers: The events in these installments, the condensed version of my book, occurred in 2002. To catch up from the beginning, these chronicles start here.

September 4, 2002. The past three weeks had been a wild ride of emotions, beginning with the jolt of my second relapse during chemotherapy. Dr. Kaminski had then lifted our spirits when he arranged for me to take a new treatment - radioimmunotherapy (RIT) - that had just been approved by the FDA and was my best chance for rescue.

Worry and fear followed since, in order to get RIT, I would have to leave Michigan, where I felt comfortable, and go to another facility, where a doctor —Dr. Doom — had snatched every hope I had by telling me that RIT might work for 10 months at most.

Panic had set in five days earlier when my blood had misbehaved so badly that RIT could not be safely administered and Dr. Doom had no backup plan. Miraculously, my blood had changed its mind the previous day. Reeling from this wild swing of emotions, Alex and I barely had the energy to hope that RIT would rescue me from the jaws of death.

As he chauffered me and my wildly multiplying lymphocytes to the hospital, we weren't sure what to expect. As approved by the FDA, RIT is given in two doses a week apart. The first dose, which I was to have that day, is considered a "test" dose to ascertain how quickly radiation clears the body, as determined by subsequent gamma scans. It has two components: a monoclonal antibody, without radiation — which I'd had before with chemo — followed by another injection that contains a small amount of radioactive isotopes. And surely the radioactive component meant Hazmat suits and lead lined rooms, which was why I fully expected to leave my little room in the infusion area after the monoclonal antibody was administered. Turns out I had to leave because there was a backlog of patients, and somebody else needed my bed.

And where were Alex and I escorted? To a supply room. Yes, a supply room, where half the cabinet doors were flung open and all sorts of medical supplies were exposed. It was a mess. Perplexed, we were told to wait there. Within minutes, a kid in jeans and sneakers arrived with the test dose. Come on, I was about to be shot up with radiation. Where was the fanfare?

There in the disarray of a supply room, I sat in the only chair. Alex held my hand. And 10 minutes later, radioactive isotopes swam through my veins, thanks to a kid who had just graduated from high school. How utterly unfitting for this brand new cutting-edge therapy! Alex and I laughed all the way home.

Our anniversary was approaching two days later, and Alex asked what I'd like to do. "Go to Hell," I deadpanned. His eyes widened questioningly. "I want to go to Hell." And so we did. Hell, Michigan, that is.

Mimicking the "Got Milk?" ad campaign, I made a "Got Lymphoma?" banner. In Hell, I placed it so that the entire sign read "Got Lymphoma? Welcome To Hell." Alex took pictures and I emailed them to several friends who saw the humor in it far more than he did. But nothing could have more clearly stated how I felt.

Next Tuesday, Nov. 30: A baseless conclusion dampens our hope

Betsy de Parry is the author of The Roller Coaster Chronicles and host of a series of webcasts about cancer. Find her on Facebook or Twitter or email her.