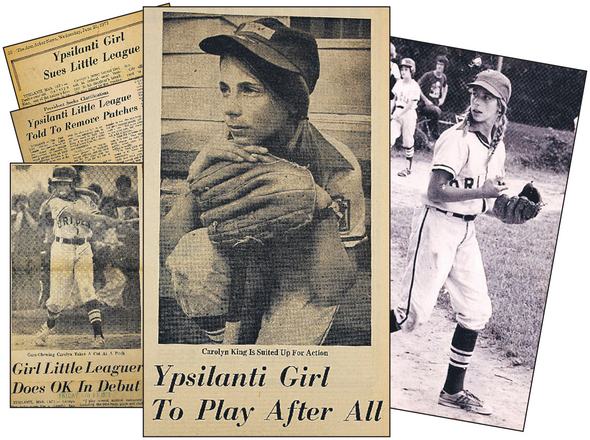

Long after she helped change Little League, Carolyn King's legacy remains alive and well

• Related content: Movie telling story of 'The Girl in Centerfield' premieres in Ypsilanti Saturday, with video

Carolyn King was 12 when letters from incarcerated male inmates began to arrive. Before long, other envelopes, some containing dolls with no heads, showed up.

It was 1973. King was a 5-foot-4 12-year-old girl with a good arm. She wanted to play Little League baseball.

What began with a simple bicycle ride to nearby Bowen Fieldhouse to sign up for a team with her brother became a complicated story that closed out national newscasts that opened 30 minutes earlier discussing Watergate.

Thirty-seven years later, King understands the fuss. She's still not entirely comfortable with being considered the pioneer People magazine made her out to be in an issue when she shared space with Sandra Day O'Connor, Billie Jean King and astronaut Sally Ride.

But at 49, she gets it.

Carolyn King is happy to see how youth sports welcome girls. "When I see a girl playing baseball now, I get a warm fuzzy. That makes me feel really good knowing that my granddaughter can grow up and have an equal opportunity to play on any team she wants to play on."

Lon Horwedel | AnnArbor.com

"When I see a girl playing baseball now, I get a warm fuzzy," King said last week. "That makes me feel really good knowing that my granddaughter can grow up and have an equal opportunity to play on any team she wants to play on. That's a pretty awesome thought."

That wasn't the case in 1973. Then King lived in a neighborhood surrounded by boys. She played pickup baseball with them and she wanted to continue that in Little League.

So she signed up. Initially, Ypsilanti Little League president Bill Anhut delivered the news King expected: Sorry, but girls aren't allowed. Moments later, Anhut walked up behind her and pinned a number on her back.

"If you really want to try out, I'm going to let you," Anhut told her. "I'm going to give you a shot."

Looking back, King knows the significance of the moment.

"It shows me that somebody had faith," she said. "He took a huge step - that was a big leap of faith for him, and I'm forever thankful for that."

Soon, officials in the Little League national offices in Williamsport, Penn., got wind that a girl was practicing with one of its chartered teams. King was an eighth-round pick of the Orioles and was again just one of the boys.

Little League officials called Anhut and made their position clear. If King kept playing, Ypsilanti would no longer be recognized as part of the Little League organization.

Local coaches and officials were conflicted. First, King could play. Then she couldn't. They wanted to be fair, but if it meant losing their charter, they had to consider the good of the entire league.

Ypsilanti Mayor George Goodman heard the rumblings of the unrest in the city's Little League program. The city funded the program, allowing teams to use city parks maintained by city workers. The city paid for umpires. As far as Goodman was concerned, a city-run league should be open to all.

Goodman, who is black and whose parents experienced hardships with discrimination in the deep South, decided that if King couldn't play, no one would.

"There was just something about it that didn't set well with me," Goodman said in a phone interview from his home on Mackinac Island.

Before long, newspapers and television stations hunkered down in Ypsilanti.

"I don't think anybody at that point anticipated it developing the way it did," Goodman said. "We weren't anticipating it being a historic moment at all because certainly, I didn't have any information about what this would ultimately turn out to be as far as the country was concerned."

In the King household, Carolyn's parents - Jerry and Priscilla - supported their daughter's desire to play baseball even though they were conservative, fundamental Baptists not accustomed to rocking the boat.

Around Ypsilanti, support wasn't nearly as unanimous. The Kings lived on the city's west side where Ypsilanti's American League teams called home.

The east side, considered more of the working-class neighborhoods, was home to the city's National League teams.

"We were (ticked)," said Brian Kruger, who played in the National League and who directed the documentary, 'The Girl In Centerfield' about King. "At first, it didn't bother us because we thought the National League was way better than the American League and now, they had drafted a girl and they were worse.

"But when Goodman announced his deal, we were like, 'Wait a minute - now it's our deal.’ "

Kruger said on the East side, Goodman was already an unpopular mayor and his decision jeopardized any hope of the city's Little League teams making any run at the World Series.

"It was all we had," Kruger said. "The west side had a lot of stuff, but the east side had baseball for the boys."

King was stuck in the middle. She was drafted because she could throw and because she was several inches taller than most boys. One of the Orioles assistant coaches, Harry Spires, worked with her on her hitting.

He knew opposing pitchers would be out to make an example of her. Although she had never faced fastballs like she would see that summer, King learned to stay in the batter's box and to dodge high and tight pitches.

"I ducked a lot," King said.

By the time her first game rolled around, King was in the middle of the media frenzy. Reporters and cameramen hung out in her front yard and called at all hours. Reporters frequently asked her to go across the street where they could get footage of her playing baseball with her younger brother, Greg.

At the time, Title IX was in its infancy and the Women's Liberation movement was in full swing. Bobby Riggs, a self-proclaimed male chauvinist, was hell bent on making an example of female women's professional tennis players, including Billie Jean King.

But at 12 years old, Carolyn King had little or no understanding of what was happening with women nationally. So when Ms. Magazine called for an interview and asked how she felt about being a women's libber, King was flummoxed.

"I had no idea how to answer that - I don't see how it could have been so strange that there were tomboys back then who just wanted to go out and play," King said. "But to ask a 12-year-old what a women's libber is, I just didn't get it."

Like King, Charles Ramsey was a west side American Leaguer. To Ramsey, who is now Eastern Michigan's men's basketball coach, the attention was stirred up by a small group of adults.

"There were no issues with the kids," Ramsey said. "I think (the situation) was unique, but that uniqueness only lasted for a few seconds before you went back to being a kid.

"I don't think we got caught up in like the adults did. I think we saw it, but let's go back and play now."

King's first game started at 6 p.m. She was dressed by noon. She arrived at Candy Cane Park to find the place packed with cameras. Boom microphones lined the fences.

People were pressed against the backstop, easily within earshot of King.

"Why don't you go home and play with your dolls?" people yelled.

"You don't belong here," others argued.

"I remembered getting booed - a lot," King said. "They would yell at me any time I ran out of the dugout and yelled at me when I ran back in."

Before the game started, Spires warned his players that not everyone supported King’s desire to play. He told her that she had the full backing of her coaches and teammates and to ignore the jeers.

All these years later, King - who has a 20-year-old daughter - says the support was invaluable.

"I've become very humbled about the amount of support and the amount of people who stood up for one little girl," King said. "I look at my daughter and say, 'Could she - at 12 - be yelled at and screamed at? Could she stand up at bat and be yelled at and screamed at or could any 12-year-old do that without wanting to run to their parents or run to their car to leave?'"

King was invited to appear on “The Soupy Sales Show” and was offered a stint as a batgirl for the Cleveland Indians. She turned down such offers, believing it would take away from the reasons she wanted to play.

"Back in the day, it was just crazy that this whole thing happened," said Jodi Slusser-Milton, one of King’s childhood friends. "Growing up in the ’70s was crazy anyway, and just being part of that without realizing what was going on is huge. You think about where we are compared to where we were back then, and it's crazy."

After having its charter pulled, Ypsilanti filed a federal lawsuit against Little League. After four days of testimony, a federal judge threw the case out on a technicality, saying it should have been filed in state court.

The city appealed the decision and King family joined the suit. Two local attorneys took the case on pro bono. In 1974, Little League changed its long-standing boys-only rule. But by the time Little League softball was introduced, King aged out of the program. Ypsilanti's charter was reinstated and has remained in good standing ever since.

King went on to play volleyball and be a cheerleader at Ypsilanti High School. She would occasionally agree to interviews. Last year, Kruger approached her about a documentary. She was reluctant, but agreed, allowing Kruger and Carolyn's Orioles teammate, Buddy Moorehouse, to go compile the project.

On Saturday, King and other former Little Leaguers will play in an all-star softball game at 1 p.m. at Frog Island in Ypsilanti, pitting the National League and American League in a game that never took place in 1973.

The game is more of reunion than anything else, reconnecting former teammates and classmates. Despite not playing that game 37 years ago, Ypsilanti's All-Stars participated in 14 other games before losing.

"We knew we were pretty good that year and we were probably the strongest team we had in a long time," Ramsey said. "But no one had any resentment. I think, as you get older, that's when you look back and say, ‘We had a pretty good shot.'

"But back then, the way we looked at it was, when (King) played she was one of the guys. When she didn't she was one of the girls."

Today, King runs a charitable foundation for former Eastern Michigan and NFL lineman Barry Stokes in Toledo. She still receives letters from girls thanking her for opening Little League to girls. In 2009, nearly 350,000 girls participated in the Little League softball program nationwide. A small number of girls - including in Ypsilanti - play Little League baseball.

"I can see what the big deal is - I can because I would be proud if it were any of my girlfriends who did this," she said. "It was just an amazing summer and I am proud of it. But I'm more proud of the fact that my team stood behind me, that I had a mayor that stood behind me, attorneys that were willing to fight for me and for a family that supported me. That's what I am the most proud of."

Jeff Arnold covers sports for AnnArbor.com and can be reached at (734) 623-2554 or by email at jeffarnold@annarbor.com. Follow him on Twitter @jeffreyparnold.

Comments

MGoYpsi

Fri, Aug 20, 2010 : 8:20 a.m.

Ypsilanti American Little League continues today through the hard work of many volunteers. Remember to support today's players.

Jim Pryce

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 11:06 p.m.

Everyone always said it was Doris Biscoe, but it was Ann Eskrigde from channel 7

stunhsif

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 8:46 p.m.

Good for her, I remember the story and was rooting for her if she could make the team based on talent. I am a few years ahead of her and as a guy was pulling for her. Physical exercise is good for the body and the mind. Back then, kids had no internet and all the other distractions to keep them from physical activity. Nice story A2.com!

Phil KIng

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 5:12 p.m.

Good story. She had to be a courageous girl, and she apparently had support whee it was most needed. As a schoolmate of Carolyn's, and someone who opposed her playing at the time, I have a very different perspective on the matter now. As Garrison Keillor said, "Having a daughter makes most men women's libbers". Looking forward to the game/reunion on Saturday, and the chance to see "old" classmates and teammates 37 years later. BTW - I believe it was Doris Biscoe who was beaned at Carolyn's first game.

ACLABT

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 4:59 p.m.

Thank you, Carolyn! I played in Little League only a couple of years later, in 1977. I was the only girl on the team but I was accepted from day one. I didn't realize how close it came to me not being allowed to play.

Jeff Arnold

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 3:11 p.m.

A correction was made to correctly spell Orioles' assistant coach Harry Spires' last name.

Jim Pryce

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 2:39 p.m.

I was a national league Ypsi kid when this was all going on. I went to school with Brian Kruger & look forward to seeing his documentary. I remember following the story on the news. What I remember most was Channel 7 sent out a reporter-Ann Eskridge & she got knocked out by a foul ball. I wish today when you drive past the parks you would see kids playing ball, all you see now are the organized programs. Jim Pryce

KBovenschen

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 12:31 p.m.

Since Carolyn and I are the same age, I remember this story well. My dad was president of the Milan Youth League (not affiliated with Little League) when the first two girls joined. I don't recall if it was '73 or '74. He coached one of them. The girls were friends and thought they'd get to play on the same team. My best friend also became the first girl to play on the boys' basketball team at Milan. Trailblazers all!

AlwaysLate

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 10:37 a.m.

Excellent story. I had forgotten all about that part of our history. A special note of appreciation should also be passed along to Bill Anhut, who has been deeply involved in many aspects of our community for many decades. He has been especially supportive in the lives and education of our local children.

Craig Lounsbury

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 10:28 a.m.

"What a great piece - and ladies, we've come a long way, but still lots of room to grow." amen. It took dragging the MHSAA in to court to get them to give girls equal rights with respect to playing their sports "in" or "out" of season.

tdw

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 8:47 a.m.

I remember my brother telling her to quit baseball at a piano reciteal when we were kids

Advance Ypsilanti

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 8:44 a.m.

It was the Ypsilanti American Little League that allowed Carolyn to try out and play for the Orioles. We are blessed in our area with two leagues (American and National). www.ypsilittleleague.org

A2K

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 8:37 a.m.

What a great piece - and ladies, we've come a long way, but still lots of room to grow.

boom

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 7:21 a.m.

Very good story. I had no idea a girl from Ypsilanti was the first to join a little league team.

Craig Lounsbury

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 6:53 a.m.

I remember the times well. I grew up with Candy Cane park an extension of my backyard. I look forward to seeing the documentary.

mdm93

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 6:49 a.m.

You rock Carolyn. Been a long time since I've seen ya, but good to know your getting the recognition that you deserve. Take care. Mark

DFSmith

Thu, Aug 19, 2010 : 5:55 a.m.

Great story!!!!! :):) It's cool to learn about history being made in Ypsilanti.