Red Simmons: Former track star, coach has legacy of creating opportunity for others

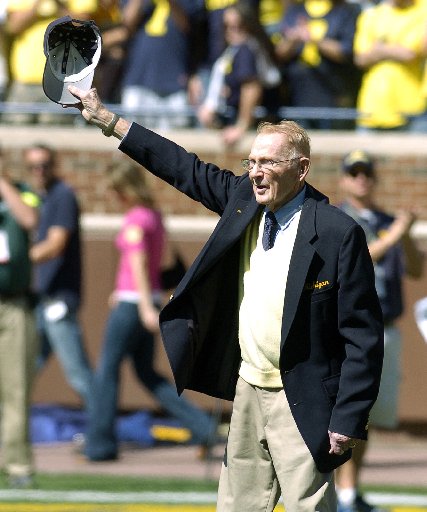

Former Michigan women's track coach Red Simmons acknowledges the Michigan Stadium crowd on Sept. 19. Simmons will celebrate his 100th birthday on Tuesday. (Photo: Lon Horwedel | AnnArbor.com)

Red Simmons has spent a lifetime paving roads of opportunity. Not for himself, so much, but for others.

He's considered the founding father of women's track at the University of Michigan, a place he hoped to attend himself, but instead opened doors to women who went on to create their own legacies - on and off the track.

Ask Simmons - who will embark on his 101st year of life on Tuesday - to prioritize his life achievements and none of what he lists has much to do with himself.

One must ask about his friendship with track legend Jesse Owens or the fact that his ahead-of-its-time weight training methods impressed Michigan legend Fritz Crisler before he will tell those stories.

Instead, Simmons - whose women's track coaching career at Michigan began only after he had retired as a Detroit city cop in 1959 - considers the achievements of others more significant than any of his own.

But mention Simmons to any of his former runners and they talk of a coaching career not built on championships, but a chance at competitive equality.

"It was the coaches around the country like Red that really gave females a chance to compete," said Francie Kraker Goodridge, who competed in the 1968 and 1972 Olympics after becoming the first female to train with Simmons at age 14.

"And that's a legacy that can't be underestimated."

A natural track star finds his form

Before Simmons taught others to run, he ran himself.

Simmons never had formal training. During his days at a small country school on Beech Road, Simmons met a man who had come from the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

The man - who Simmons refers to as Mr. Pontius - found local farmers to roll out a place in fields for Simmons and his classmates to run. The farmers also carved out pits for the high jump and long jump as well as constructing meager hurdles that gave students a full-service training ground.

Simmons was a natural.

"(The ability to run) was something I had," Simmons said in an interview last week. "I was never trained, never coached. It's just something I inherited."

Pontius saw potential in the young runner. He traveled to Simmons' house by bicycle and informed his parents that their son had the ability to be a great athlete, but would have to enroll at nearby Redford High School.

Because of the duties most boys had on family farms, Simmons was one of just four students from his class to continue on to high school. His prep track career put him on the radar screens of college coaches at Michigan and Michigan Normal College (now Eastern Michigan University).

Success at Michigan Normal School

Michigan men's track coach Stephen Farrell was the first to call, offering Simmons a place on his team. At the time, there were no athletic scholarships, leading Farrell to offer Simmons a job at a campus fraternity house to help pay for his schooling.

Simmons had fallen in love with Michigan the first time he visited at age 17. His first trip to Ann Arbor came in 1927, when he hitchhiked from Redford for the opening of Michigan Stadium. Coming from a small high school, Simmons was amazed at the university's facilities and at the popularity of Michigan's athletes.

"I thought to myself, 'What a wonderful place,'" Simmons recalled. "I knew I wanted to go to the University of Michigan."

But when the stock market crash of 1929 hit, the job Simmons had been promised was lost. It wasn't long before Michigan Normal track coach Lloyd Olds got word that Simmons wouldn't be attending Michigan. He let Simmons know that that tuition in Ypsilanti totaled just $18.50 a semester. Olds then arranged a loan that would allow Red begin classes. Simmons repaid the loan 25 years later.

Each day, Simmons hitchhiked from Redford to Ypsilanti, where he'd spend the day in class and running track.

As much as Simmons loved to run, he struggled academically. His parents didn't have the money to pay for books, putting Red at a disadvantage in the classroom. Charles McKenny, Michigan Normal's president, wrote a letter to Simmons' parents informing them that Red wasn't cut out for college life.

But knowing what Simmons' athletic abilities could lend to Michigan Normal's track program, Olds and James "Bingo" Brown - the school's dean of men - intervened, asking McKenny for a second chance.

Simmons improved in his classes, and he found a job washing gym mats for $2.50 a week. Simmons excelled on the track team, becoming part of a mile relay team that eventually qualified for a spot in the prestigious Penn Relays.

Facing Jesse Owens and impressing Fritz Crisler

During one meet at Michigan in 1930, Simmons set the venue record in the low hurdles - a mark that remained intact until 1935. That year, a young Ohio State runner named Jesse Owens came to Ann Arbor, setting four records - including in the low hurdles.

Two years later, Simmons met Owens, striking up a friendship that included the pair appearing together at exhibition track meets together. Simmons figures he ran against Owens some 20 times over the years, never winning.

Simmons continued to run even during his 25-year career as a Detroit police officer that began in 1934. He joined the department's track team, often out-running competitors half his age. His training soon included weight training - a concept that was just becoming popular in the late 1950s.

Michigan athletic director Fritz Crisler was intrigued. He offered Simmons a teaching job at Michigan, hoping to introduce the university's athletes to Simmons' training methods. Over the next three years, Simmons taught weight training, first aid, boxing and wrestling classes - all while completing his master's degree in physical education (now kinesiology).

But in 1960, Simmons witnessed something that bothered him. During a trip to the Rome Olympics, Simmons and his wife watched as the United States women's track and field competitors struggled.

The father of women's track at Michigan

Simmons wondered how he could change that. He encouraged his wife, Betty, a physical education teacher at Slauson Middle School in Ann Arbor - to pick her best student. She chose 14-year-old Francie Kraker, who was intrigued by the offer to train privately with Simmons.

At the time, competitive opportunities for women in track and field were non-existent. Other than local AAU club championships, there were no competitive outlets. And here was this man asking Kraker if she'd like to train for the Olympics.

"It was pretty overwhelming," Kraker Goodridge said last week.

Goodridge, who retired last April after working as a recruiting coordinator at the Michigan School of Music, went on to become the first Michigan-born woman to be named to the U.S. Olympic team, qualifying in the 800. Four years later, she traveled to the Munich games to compete in the 1,500, setting the second-fastest time ever posted by an American (4:12.76) in the semifinals.

She'd later coach track at Michigan and help begin the women's track program at Wake Forest after working as an athletic administrator at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee following the passage of Title IX.

But training Kraker was just the beginning for Simmons. Within 18 months, he had built a large collection of young women by traveling to local schools looking for girls interested in running competitively. The club - Ann Arbor's first female track club of its kind - became known as The Michigammes - a collection of runners that over time, produced seven national champions as well as numerous state track and cross country champions.

"It was just such a unique opportunity," Kraker Goodridge said of being part of Simmons' club. "I think that's why all of us leapt at it, because there was nothing else of its kind around and we were all excited just to have the chance."

But finding a place for his women's track club to train was difficult. Simmons went to Michigan athletic director Don Canham, asking if his girls could use the same track as Michigan's men. Canham hesitated. He certainly didn't want women getting in the way. Over time, Canham conceded, creating room for what would eventually become the school's women's track program.

"I didn't know I was making history," Simmons said. "It was just something I enjoyed doing and now, it's like, 'Gee - that's the guy that started women's track.'

"At the time, I didn't know what I was doing (historically), I was just the guy leading the women's track team. It takes 30 or 40 years before you realize that I was really something."

In 1972, Title IX was enacted. The goal: Women would have the same opportunities as men. When the law went into effect, Canham knew he'd have to start a varsity track team. He knew Simmons had to be his coach.

He offered Simmons the job in 1976 and a starting salary of $7,000. Simmons took the job, but only if his wife could assist him to keep him from traveling alone with an all-female team. Canham agreed, taking care of Simmons' wife's expenses in exchange for Red's leadership.

The team gained varsity status in 1978 and Simmons remained at the helm until 1981 when he retired at age 71.

Like he had with Kraker, Simmons provided detailed teaching methods to his runners. He also served as a father figure and teacher.

"He was a walking proverb, but at the same time, he was still very encouraging," said Michigan women's coach James Henry, who worked with Simmons as a volunteer assistant. "I think the girls knew (Simmons) was a friend, but they also knew they had to keep that line between coach and friend."

More medals as a Senior Olympian

Since retirement, Simmons remains active after winning four gold medals in the 1995 Senior Olympics before finding more success five years later at the age of 90. These days, his exercise regimen includes walking the steps at Crisler Arena five days a week. In 2009, Simmons was given a Lifetime Achievement Award by the university, honoring his legacy in helping establish the school's women's track program.

Simmons, who continues to fund several scholarships and awards, remains a staple at Michigan sporting events. He regularly dons his beloved maize and blue while sitting side-by-side by his wife, Lois, who he married a year after Betty passed away.

His slower pace of movement is about the only noticeable sign of age outside of his diminished ability to hear, which is aided by an electronic device. His hair, always perfectly combed, still shows hints of the red that inspired his nickname.

Simmons is amazed at how quickly his later years have passed and how much is involved in reaching a milestone birthday. Over the next two weeks, he has five celebrations to attend.

And as he prepares to turn 100 on Tuesday, Simmons said his contributions to women's track are what he'd want to be remembered for. It has taken all of these years, he admits, to understand the role he had in giving female athletes at Michigan the opportunities they have today.

"Of course he was making history but I don't think he sensed it at the time," Henry said. "When you're doing something that's never been done before, you're just doing it. I don't think he ever stopped and said, 'We're making history.'

"He just wanted to give females the opportunity to run at the college level, and it hadn't been done before. It's like if there's not a club today, you start one and it's there tomorrow."

Simmons keeps tabs on his former runners. He remembers them not for what they did on the track, but what they have done in the years since. He will often run into them or hear of their achievements from his network of friends, providing him the satisfaction that comes with a life well lived.

"You don't realize until it's over that I was part of this girl's life," Simmons said, his infectious smile crossing his face. "When we sit down and get these letters from these girls, we know we were part of them, we were responsible."

Jeff Arnold covers sports for AnnArbor.com. He can be reached at jeffarnold@annarbor.com or 734-623-2554. Follow him on Twitter @jeffreyparnold.

Comments

jim Moyes

Sun, Jan 3, 2010 : 1:01 p.m.

Well deserved story of Red Simmons but I have to somewhat spoil the party somewhat by challenging the fact the Red won both state hurdles championships in 1928. Those were won by Detroit Northeastern and later EMU legend and Simmon's team mate Eugene Beatty. Beatty also won the Detroit PSL championships in 1928. As a side note I believe that one athlete who did win a state title in 1928 may still be alive. His name is Robert Sampson and he perhaps will turn 100 years old (if not already) and he competed and won the high jump for Detroit Cass Tech. Wouldn't it be great if Bob could also share in the joy of being honored with his 100th birthday. Anyway--- great story.

DaviesHouseInnGeorgetown

Sun, Jan 3, 2010 : 10:53 a.m.

Happy Birthday Red! As Chair of Volunteers for the Millie Schembechler Memorial Golf Outing, I had the privilege of working with Red for the 8 year run of this event which raised $5 million to endow a Chair of Research for Adrenal Cancer Research. He always brought his smiling face, encouraging words, positive attitude, and exceptional gratitude; he was the spark plug with the 144 volunteers committed to the event. Thanks Red, you made my job easier, and so much more enjoyable. He is a dedicated volunteer to many causes and sponsor of many scholarships and awards to recognize and encourage achievement. He is a role model for us all: a true gentleman, an innovator leading trends, and an awesome model for a rewarding life in senior years maintaining a level of health, fitness, and activity to be marveled. I want to be Red when I grow up! My sense is Red will celebrate those 100 years, pacing them 20 years at time at those five celebrations scheduled to honor one amazing life. Happy Birthday Red!

Pete Winer

Sat, Jan 2, 2010 : 11:57 p.m.

Wonderful to read about Red! I recall taking PhysEd electives (Red's "physical torture" classes) for two years to get in shape for Marine Corps ROTC summer camp at Quantico, VA, summer of 1960. I didn't realize it at the time, but Red was teaching rather advanced training techniques in those days that have stood the test of time. Summer Camp was demanding, of course, but Red's conditioning techniques made a big difference, thus enabling my success. After graduation/commissioning in 1961, I spent 25 years on active duty as a Marine officer. My hat's off to Red's contributions to the role of women in athletics. He overcame many of the same issues we overcame in the mid-70s as women were allowed to enter nearly all occupational fields of military service. The women of today that routinely experience the benefits of team competition at a young age have a distinct advantage over their non-athlete predecessors as they enter adulthood well prepared to take their places in our competitive job market and society. Congratulations Red on making a difference in our lives!

A2 Extra

Sat, Jan 2, 2010 : 7:51 p.m.

Red and his wife Lois are two of the most caring and dedicated people you could ever meet. I hope you have an incredible 100th Red...we love you!

Richard Retyi

Sat, Jan 2, 2010 : 5:37 p.m.

I worked with the women's track and field team when I first arrived at Michigan and quickly became aware of Red Simmons and his legendary story. He's a fixture at U-M volleyball games and around the athletic department and he always has a kind word and a smile for anyone who says hello. Happy early 100, Red!