Bo Schembechler had Barry Larkin's number long before it was retired by the Michigan baseball program

Former University of Michigan baseball great Barry Larkin, left, thanks those in attendance on Saturday for the Michigan-Ohio State baseball game at Michigian's Ray Fisher Stadium. Larkin was honored by the Wolverines by becoming the sixth former Michigan player to have his number retired. Lon Horwedel | AnnArbor.com

The visitor usually took the same detour on his way to work. He'd slip inside the gates of Ray Fisher Stadium and onto the field, walk down the first base line, pass behind the plate and make his way toward the third base coach's box.

Once he got within proximity of Barry Larkin, the visitor - whose identity was sometimes concealed by the hood of his parka - would stop to do nothing more than to heckle the young Michigan shortstop.

"Larkinnnnnnnn," Bo Schembechler would growl under the heavy coat that covered his familiar face.

Schembechler, by the mid 1980s firmly established as one of college football great coaches, was the primary reason Larkin landed in Ann Arbor. Although the two never developed the kind of teacher-mentor bond Schembechler envisioned when he recruited an all-state defensive back, his impact on Larkin remains invaluable to the 12-time National League All-Star.

Larkin grew up in Cincinnati, which, like nearby Columbus, had a long-standing hatred for that damned school Up North. Betraying his upbringing, Larkin always envisioned himself at Michigan, where he'd get the chance to wear the school's famed winged helmet.

Once in Ann Arbor, Larkin considered being a two-sport athlete. He could spend the fall playing for Schembechler before shifting to baseball after the New Year. But when Schembechler decided to redshirt Larkin as a freshman, Larkin saw the chance to devote his full attention to baseball.

His singular focus led to an 19-season Major League career that culminated Saturday night when the former Cincinnati Reds shortstop became sixth Michigan baseball player to have his jersey retired. Larkin - who wore No. 16 during his three years with the Wolverines before he was drafted in 1985 - was honored in a pregame ceremony three years after being inducted into Michigan's Hall of Honor.

By having his number retired, Larkin joined a small fraternity that includes Larkin will join Moby Benedict (No. 1), Bill Freehan (No. 11), Jim Abbott (No. 31), Don Lund (No. 33) and Ray Fisher (No. 44).

His focus also led to Schembechler’s teasing.

Baseball, according to Schembechler, was a sissy sport, and he wanted to make sure Larkin knew how he felt. So on his way from Michigan's athletic offices to the school's indoor football facility, Schembechler detoured through Ray Fisher Stadium intent - if nothing else - on letting Larkin remember he hadn't been forgotten him.

At times, he'd find a spot in the seats and yell at Larkin, who did his best to convince his teammates that the man tucked under the parka was, indeed, the school's old-school football coach. Even if he wasn’t sure at first.

"He looked like Darth Vader with that hood on," Larkin recalled on Wednesday. "I'd just look over and say, 'Who's that?'"

Schembechler, a left-handed pitcher who had played collegiately at Miami (Ohio) would tell Larkin every chance he'd get about his wicked curveball. He often boasted if given the chance, he could strike Larkin out.

Schembechler told Larkin he would use intimidation, fire one high and tight to get Larkin off the plate and then go to a back-door curve to finish the job.

Larkin would just laugh. But deep down, he knew Schembechler was a big reason he had landed where he had. He didn’t respond to any of Schembechler's verbal jabs.

"I would just look at him," Larkin said. "But I never said anything because it was Bo, for crying out loud. It was Bo Schembechler."

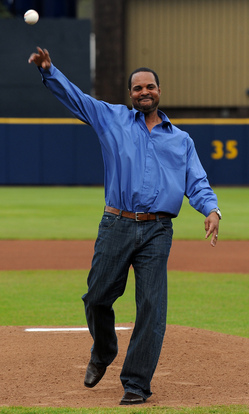

Former University of Michigan baseball great Barry Larkin throws out the first pitche before Saturday night, May 1st's Michigan vs. Ohio State baseball game at U-M's Ray Fisher Stadium, where Larkin was honored by the Wolverines by becoming the sixth former Michigan player to have his number retired. Lon Horwedel | AnnArbor.com

Like any freshman, Larkin had to make his share of adjustments. He was in a new place, at a large university and surrounded by people he didn't know. While it was Schembechler that had drawn him to Michigan, Larkin went to variety of people to help acclimate himself, getting guidance from everyone from Michigan football players to the team's longtime equipment manager Jon Falk.

He found an easiness with Casey Close, his first roommate at Michigan who now works at Larkin's agent. Close grew up playing baseball in Columbus - about 100 miles from Cincinnati. Despite their proximity to one another, the two had never met before being thrown together as two out-of-state freshmen.

The two quickly adjusted to college life. Larkin was quiet and reserved, keeping to himself. Over time, though, his personality surfaced.

"The more you got to know him, the more you saw this guy who was genuine, funny, witty and gregarious," Close said in a phone interview Friday. "He was really a likable guy that really seemed to fit in well with everyone he was around."

As the only African American on Michigan's baseball roster, Larkin found a caring coach in Bud Middaugh, who, along with his wife often helped Larkin work through new experiences.

But unlike Schembechler, whom Larkin could joke around with, Middaugh was the boss and his baseball success was predicated on Larkin playing well. With Larkin, Middaugh balanced a tough love with a caring spirit.

Larkin, who was drafted by the Reds as a center fielder, had so much natural ability. But it was crude and required fine-tuning. But there was so much more to Larkin's game that Middaugh saw - the speed, the arm strength and the athleticism - that could be blossomed into a top-notch shortstop.

"The first time I saw him play, he had three balls hit to him," Middaugh recalled last week. "Two he booted and one he threw away. But I gave him a full scholarship that night, so that shows you what kind of scout I am.

"But Barry was kind of special."

At Michigan, Larkin developed into a two-time All-America selection while helping lead the Wolverines to two College World Series appearances. Close said perhaps more than anyone else in Michigan baseball history, Larkin elevated the Wolverines from a good program to a great team recognized on a national stage.

The better Larkin got the more the Wolverines won, preparing Larkin for a big-league career that lasted nearly two decades. Larkin - now 46 - was part of Cinncinati's 1990 World Series championship team and won the National League's MVP award in 1995 before becoming the first shortstop to hit 30 home runs and steal 30 bases a year later.

Since retiring in 2004, Larkin has worked as a front-office consultant with the Washington Nationals, as a philanthropist and now as an analyst with the MLB Network.

He remains at heart, a lover of the game, teaching baseball across the world to young players through cultural exchange program he developed at his baseball academy he developed after his playing days.

Although his dreams of playing football at Michigan never materialized, Larkin is one of Bo's Boys, carrying pieces of what he learned at Michigan and from Schembechler.

"The things I did as a professional player, I think it's an extension of the fundamentals that were stressed as a collegiate athlete at Michigan," Larkin said. "I think they go hand in hand. The foundation of what I did as a pro was started and solidified when I was in college, the learning environment and the ability to grow as a person and just mature."

Jeff Arnold covers sports for AnnArbor.com and can be reached at (734) 623-2554 or by e-mail at jeffarnold@annarbor.com. Follow him on Twitter @jeffreyparnold.