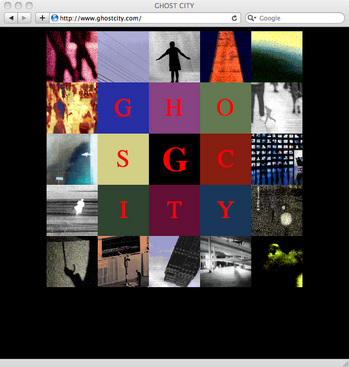

This week's web picks: Ghost City, Wikipedia books, City Data and more

I can honestly say I haven’t a clue what this site means. And that’s why I like it, though I haven’t completely given up trying to figure it out. T

here are websites that exist as nearly pure electronic works of art. Their designers are tech savvy in ways that mean little to you or me, so much so that their imaginations overflow. They love to create patterns, to shape and sequence pixels. They love to provoke, to express, to confuse and to overwhelm viewers with unusual, often kinetic displays of visual originality.

And they like to play. Do you want to play?

The Ghost City website is a place to play and explore.

In Ghost City, you’re not even sure where to click, let alone what expect. You’re not even sure why you’re there, or even if you like what you see. There’s no way to know why this frame comes up, or where to go from there. Or this one.

Why are you wasting your time? Why am I wasting your time? Maybe because the web is much more than a source of verbal or intellectual content. It’s also a sensual medium, barely 20 years old, and its users are still entranced by its expressive powers, its ability to do things no other medium can do.

Explanation is too academic for this web artist’s school of thinking. Hey, who is this guy? Maybe one of you will let me know.

Inside the information-spiked labyrinth called Wikipedia is a function, barely visible on the home page, that lets users create books that are compilations of Wikipedia articles. The book is then stored as a separate link, controlled only by its creator.

But it can also be given weight as a handsome, perhaps large, PDF printout; and even better, it can be printed and bound, for a fee, as an actual book with heft, whose cover you choose, with your name shown as “author.” I’ve done it and it looks good. A 300-page book costs about $17, but extra pages of sources add up.

Now why would anyone want to create, let alone publish, such a book? For the simple reason that coverage of the topic, such as you choose to make it, doesn’t exist. Your molehill may really be that mountain! You can create a book about cupcakes, about your grandmother’s birthplace, a forgotten harmonica player, fishing in Arizona, female aliens in movies or a political battle in a country no one remembers.

The fun is in finding Wikipedia articles that relate, or that you believe relate, to any aspect the topic you want to cover. Mine was about Free Speech — not that exciting. But look at some of the titles and topics people have written about. Your book can be read, downloaded, or printed out by others, if they can find it: Wikipedia’s indexing system isn’t exactly user-friendly.

Making a book is easy and step-driven, with help always a link away. Putting aside Wikipedia’s accuracy, which studies have shown compares well with the Britannica’s, your book could be useful to an organization you’re involved with, to friends, club members, beginning researchers, libraries or businesses. Or it could just be a trophy publication for someone with free time, a roving mind, a dream of adding one more category to the world — and a penchant for creatively re-imagining someone else’s work, a little bit like Steve Jobs did.

Who exactly lives in Paradise? What’s the crime rate there? Paradise, Penn., that is. Or Paradise, Texas. How many unmarried people over 15 live in Paradise? On City-Data you can find these facts and more — nearly everything measurable and recorded — about almost every village, town and city in the U.S. Not just as textual data, but in maps, charts, financials, links, photos, graphs or dynamic search engines.

You’ll probably find out more than you should know, or want to know, unless you’re thinking of moving there, or doing business there. Paradise, Texas has only about 529 people, but you can still learn that the median home price is $84,308, its residents were 6.1 percent Hispanic in 2009 (compared to Texas' 37 percent), 20 percent of them worked in educational services (compared to Texas' 5 percent) and that its ozone levels were about 46 percent worse than the U.S. average.

Not to pick on this small town: these are simply examples of the detail you can find for any town, even the large cities, with hundreds of public and private schools. Realtors, parents, researchers, job seekers, politicians, salesmen and know-it-alls should find this information valuable. I bet I know what town you’re going to look up right now! When you’re done, you can be sure of only one thing: you won’t be getting the whole story.

These days, every other thing seems to “go viral.” But how do ideas spread? Like oil, like a disease, like nuclear fallout, like DNA? No one really knows. Truthy represents one of the more serious attempts to examine, and establish, the new science of memes.

Richard Dawkins coined this term in 1976 to describe units of cultural transmission — carriers of ideas — as a system modeled metaphorically on genetics. Memes are usually expressed as phrases, words, short statements or hashtags. Even ideas qualify, if they’re describable enough — and you agree with the description.

You can’t see memes, but you sure can devise ways of studying and embodying them. Truthy exposes their expression as Tweets, maps how they spread in visually mesmerizing “diffusion networks, ” offers user and timeline statistics about specific Tweet destinations like @barackobama, and posts videos of Tweet distribution patterns.

If all this doesn’t make as much sense as it’s supposed to, you’ll find it earnestly explained by its Indiana University faculty and student perpetrators on their Projects Page. Tweets are hardly the only way memes are studied: The Daily Meme offers other ways of looking at them, and Quickmeme shows a more playful approach. But memes are nothing if not playthings. Whether you’re a sociology professor, a branding entrepreneur, a rock star, a pundit or a poet, haven’t you noticed that more and more people are saying what you thought you had said?

Paul Wiener of Ann Arbor was a librarian for 32 years at Stony Brook University, in Long Island, N.Y., where he managed the English Literature, Art and Film Collections. He may be reached at pwiener@gmail.com.

Comments

ArgoC

Sun, Apr 1, 2012 : 3:44 a.m.

This is the first time I have seen this feature, and I just spent a very educational hour looking at the suggested sites. I hope future posts are half as fascinating as this one. Thanks!