U-M Press launches Open Text Project with gift to the autism community

The University of Michigan Press is in a unique position to honor National Autism Awareness Month by offering…awareness.

The university’s publishing arm kicked off its brand-new Open Text Project on April 1 by making its 2009 title “The Accidental Teacher: Life Lessons from My Silent Son” available in its entirety, for free, during the month of April. In it,

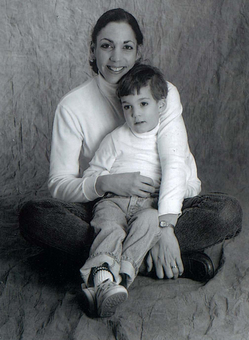

Detroit-area mom Annie Lubliner Lehmann tells the story of raising her son Jonah, who was born with autism in 1983 — well before every publication from the New York Times to the Wall Street Journal started reporting the dramatic increase in autism-spectrum diagnoses that continues to baffle doctors. “Jonah, it turned out, was at the starting gate of a growing epidemic,” she writes.

Groping around in uncharted territory is an unbelievably wretched place to be when the well-being of your firstborn hangs in the balance. There were experts, special schools, short buses, mainstreaming, therapists, educational plans, books, total-involvement programs, well-meaning friends and family, hired help and the 24/7 efforts of the Lehmanns themselves, but none of these interventions led to a cure or even a change in circumstance that Lehmann could label as “progress,” really: At 26, Jonah remains nonverbal and in need of constant supervision.

And this is where the life lessons come in. Jonah lives in a home with roommates and caregivers, participates in activities he enjoys like swimming and hiking and even delivers cases of bottled water in a small business that Lehmann set up. As she wrote in the New York Times just after the book was published, “I am grateful that he has some of the same things I want for my other two children: love, safety, physical comfort and access to favorite activities.”

This is not a book that comes with the neat label of “success story,” implying a dramatic conclusion and concrete steps to provide the reader with a repeatable experience. Instead, it’s something that is sheer relief to anyone who has come up against a challenge that proves to be simply unconquerable in the traditional sense: company. And not just drop-by-the-hospital or bring-a-casserole-once kind of company, but rather the kind of in-the-trenches kinship that frankly acknowledges the unremitting guilt and uncertainty that comes with every choice.

Lehmann said she wrote the book from a parental perspective, but “I thought about it as being more for teachers, because they rarely get a parental perspective. It would be a realistic view of the raising a child with autism who remains, despite Herculean effort, severely impaired. It seems like I hear from parents in general thanking me for telling it like it is, instead of these happily-ever-after endings that are often in the literature. Anyone who works with an individual with autism is dealing with his or her parents, and should have some insights on what parents are dealing with on a day to day basis. It’s an honest look at what life is like for an entire family.”

Maybe the most enjoyable part of the book is watching Lehmann herself blossom from a timid mother who faithfully heeded her pediatrician’s advice not to take her baby out in public (was there ever a better recipe for postpartum depression?) to a firm and brave “autism-mama” who, after her request for a candy-free aisle at her regular supermarket went unheeded, regarded the mess of an overturned display as a valuable lesson for the store’s proprietor. To anyone who has discovered that the address on their permanent home in this world is not on “Normal Street,” it is a profound, exhaling comfort to meet the neighbors.

But these stories aren’t just valuable to fellow travelers along the autism journey. I will probably never look at an onerous airport line again without thinking of the time Lehmann, struggling to keep Jonah’s hyperactivity from infringing on the personal space of strangers, asked to move to the head of the line. She was told they would have to wait “like everybody else” — until she stepped back and let his screaming, jumping, banging and touching prompt a call to security, who escorted the family through the line with sudden alacrity.

We members of “everybody else” are probably all guilty of one or two bubbles of low-grade resentment over something we see as special treatment, judging its appropriateness on the basis of a slice of activity we may see in the airport or supermarket, but that story — which takes up just one paragraph of the book’s 15 chapters — puts the slice in its proper home against a larger backdrop.

“People just don’t get it,” agreed Lehmann. “The average person gets a snow day, and it’s great. It’s like down time, you get to sleep in, maybe go back to bed, wear your pajamas all day, get things done around the house. But when you have a parent with a severely disabled child, and no help is coming, and school is closed, it becomes the most nerve-wracking kind of information. Everyone else is excited, but you’re pulling your hair out thinking, ‘What am I going to do for the next 15 hours?’”

In its print form, this book does what all books do: Provides a vehicle by which the author can transfer her thoughts and experiences to the reader. Making it available for free online perhaps increases the number of readers and certainly increases the ease of the transfer, since there’s no purchase involved. But the Open Text format, powered by an online platform called digress.it, does more: It turns the book into an online community.

One chapter is presented per page, and a floating window scrolls down the text with the reader, offering a chance to add and read comments at each paragraph with a simple click. Said U-M Press’ trade marketing manager Heather Newman, “It’s an effort on our part to present books in a new way — we’ve been presenting books electronically for a long time in a couple of different ways, but this is our first opportunity to let people interact with this book, especially on this level. It kind of turns the whole book into a blog.”

Part of the reason U-M chose digress.it, actually, is because it’s based on the popular blog hosting tool WordPress and therefore familiar to many Web-based readers already. “Not to dip into geekspeak,” warned Newman with a laugh, “but digress.it is a really robust platform for blogs. This is essentially the process of dividing the books into chunks — chapters — that become like blog entries. But in blogs, you’re stuck with commenting on the whole entry, so what this does is let you comment paragraph by paragraph. And you can see that this doesn’t look just like a blog, it looks more like a book with a table of contents and chapters.”

But wait, there’s more. “And on the academic side, there’s a hope that it will be a boon for the peer review process: because we also have the opportunity to password protect it, we can post parts of books and have members of the peer community post feedback. It’s a streamlined way for people to leave comments in ways that haven’t been tried yet. … We have no plans as yet to put all of our review copies on there. But in terms of the public, we hope it will provide us with feedback on how people want to interact with our books. Books are not static anymore. We are already providing a bunch of digital media for many of our books already, and this is one more way that people can interact with the books we publish.”

What effect might this have on print sales? “We chose this project in particular, in relation to National Autism Month, because we were willing to accommodate any loss,” said Newman. “But realistically, these are not books that are going to be posted forever, and I think that the opportunity to comment is unusual enough to get people (to look at them). But for people who want the whole book, I think they’ll prefer to buy a print copy or one that they can take with them, like on Kindle.” In fact, she thinks it might end up actually helping paper sales — if people read it and like it, they might be more likely to read other books from the author, or from U-M Press, or buy copies of the book they like to give to friends.

But all of that remains to be seen in this exciting new publishing frontier. For now, Newman is just pleased to be able to bring a great book to anyone who might benefit from it. Of choosing this title to launch the Open Text Project, she said, “Clearly we wanted an author who was interested in interacting with her readers, and Annie’s been wonderful with that. She’s interested in what people have to say, and she’s really involved with various groups. It was easy to select her. And as far as the book itself, National Autism Awareness Month is a big deal for us because of publishing the title. This is kind of our present to the autism community.”

It’s Lehmann’s gift, too — she has donated all of her proceeds from the book to autism research, both because she always felt it was a project to benefit the community and because she has no interest in profiting personally from her son’s disability. “My hope is that it helps — whatever it adds to anyone’s information about the autism experience, that’s what I hope it does. If it helps a parent who has a severely impaired child who isn’t getting better, I’m glad to hear that. If it’s a teacher who goes into (meetings with the parents of autistic children) with a different perspective, or if it’s the money that helps with research, then that’s what I want it to do.”

You can read Annie Lubliner Lehmann's “The Accidental Teacher: Life Lessons from My Silent Son” through University of Michigan Press' Open Text Project.

Annie Lubliner Lehmann will speak on her book and answer questions from 5:30-7 p.m. Tuesday, April 27 at the Hatcher Graduate Library Gallery/Room 100, University of Michigan.

Leah DuMouchel is a free-lance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.