U-M professor Douglas Trevor talks about his novel, 'Girls I Know'

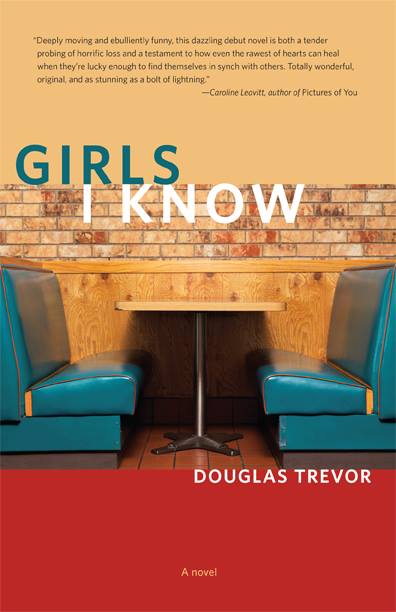

But once you start reading about Walt, the novel's 29-year-old, Boston-loving main character, and his beloved regular breakfast place, The Early Bird Cafe, that empty booth, the centerpiece of a cover bathed in primary colors, starts to look portentous.

With good reason. Walt, a lapsed doctoral candidate at Harvard, previously escaped his Vermont hometown - where his grandmother now takes care of his multiple sclerosis-suffering mother - to study poetry; but after his academic pursuits stall, and he establishes a routine in which he subsists on odd jobs (like dry cleaner employee and an apartment building superintendent), he finds himself surviving a shooting at The Early Bird Cafe.

In the wake of this tragedy, Walt's relationship with The Early Bird owners' 11-year-old daughter, Mercedes, and a self-absorbed, privileged female undergraduate named Ginger, deepens and evolves.

In anticipation of Trevor's upcoming reading/signing at Nicola's Books, AnnArbor.com asked some questions about "Girls I Know."

Q. What was the seed of the novel's story for you?

A. There were a few seeds. One was the desire to write about characters from different walks of life: different ethnic, racial, and class backgrounds. I wanted to do a much smaller version of something like John Dos Passos's USA Trilogy (1930-1936). I thought focusing on a restaurant would be a manageable setting, and I thought of a restaurant shooting as the central event around which my novel would pivot, because I couldn't think of any other novels structured around such an event, and I thought it would be interesting to try to write one.

PREVIEW

Douglas Trevor, author of the novel “Girls I Know”

- What: Trevor, an associate professor of renaissance literature and creative writing at U-M, previously won the 2005 Iowa Short Fiction Award, and was a finalist for the 2006 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for First Fiction, for his story collection, “The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space.” In Trevor’s new novel, “Girls I Know,” a 29 year old lapsed doctoral candidate in English survives a shooting in his favorite Boston breakfast restaurant, altering his relationships with a privileged, ambitious undergraduate student and a suddenly orphaned, silent 11 year old girl.

- Where: Nicola’s Books, 2513 Jackson Ave. in Ann Arbor.

- When: Tuesday, September 10 at 7 p.m.

- How much: Free. 734-662-0600 or www.nicolasbooks.com.

A.

It was very difficult. Patriot Day is a day unique to New England, and when I lived in Boston I absolutely loved the festivities surrounding it. "Girls I Know" begins in the Back Bay before moving into Cambridge and then Watertown, so the book follows a path similar to that taken by the perpetrators of the Marathon Bombings. It felt a little eerie, going to Boston a short time after the attack to promote the novel. But the response of the city to the attacks reminded me of why I had been drawn to explore and write about Boston in the first place, and the feedback I received from Bostonians in response to "Girls I Know" was incredibly warm, I think because of its depiction of the city. That said, the Boston portrayed in "Girls I Know" is actually a much more divided city than it was in the days and weeks following the attacks.Q. Did you struggle with the novel's structure - specifically, the point of entry? (Trevor introduces readers to Walt and the people in his daily life in some depth before the violence occurs.) It seems like it would be tempting to start with the shooting and then go backwards in time to fill in what precedes it.

A. I tried the book that way but it didn't seem to work. I think I wanted the reader to care about, and know, the characters before the shooting took place. So I experimented with several approaches before deciding - based in part on my friend and colleague Eileen Pollack's strong insistence - to allude to the shooting in the opening of the book but then wait to show it. That way the reader knows something horrible is going to happen, but is permitted to watch the early action of the novel unfold without feeling restricted by flashbacks and reminiscences.

Douglas Trevor

A.

Yes. She is quite abrasive early on, and I think it's asking a lot of readers nowadays to wait and see how an immature character might evolve. The risk is always that a given reader might just put your book down. But Ginger is just one of what ends up being three central characters and she does evolve and soften, I think. At the same time, I encounter driven, focused young people like her all the time - at least a handful every year I have taught - and a part of me really admires people like her, who work hard and pursue their projects with some abandonment. Perhaps, as a teacher, I'm more inclined than the average civilian to be patient with 20-year-olds like her. A funny side note: when the short story "Girls I Know" first came out, now some years ago, I had a number of female friends ask if I had based Ginger on them. So not everyone finds her to be absolutely objectionable. Since the novel has appeared, many of the emails I have received have focused on her. I hope that she is, if not universally likable, then at least interesting. But I also think the tendency to evaluate characters based on whether or not we like them is a mistake. I don't like Humbert Humbert, but I love Lolita.Q. You earned your doctorate at Harvard, but it's not your hometown. Were you nervous about setting the book there?

A. I was nervous, and in part because of this nervousness, I decided early on that Walt Steadman, the central character, would be from Vermont. That way I wouldn't feel responsible for getting everything right, so to speak. But I also wanted to take some risks, and by the time I ventured into the portions of the book narrated by Mercedes Bittles, the 11-year-old who really is from Boston, I felt ready to see the city from her perspective.

Q. What kind of responses have you heard from readers so far?

A. The response has been overwhelmingly positive. "Girls I Know" is basically a book about people who reach out, with varying degrees of success, to other people they barely know: a young, 11-year-old girl who is grieving the death of her parents, a survivor of a grisly restaurant shooting, a young woman whose life is spiraling out of control. I think readers today - in a world that is increasingly fractured and in many ways, paradoxically, more solitary than ever - understand the stakes of such gestures. And the book emphasizes the importance of education: of helping young people learn the value of the written word, and of the positive benefits that come with participating in the education of others. Those central themes have been well received. But the humor of the book, which made it possible for me to write it, has also been appreciated by some, and that means a lot to me, because attempts at humor can be idiosyncratic and can make a writer feel very exposed and vulnerable.

Q. Do you map out your stories before you launch into the writing process?

A. I do outlines fairly regularly as I am writing, but they change quite a bit as I proceed and I want to see them change. If a story unfolds as I first imagine it unfolding, then it seems to me that something must be wrong: that the characters aren't establishing themselves enough to push back against my designs. By virtue of this outlook, I tend to write a lot of drafts and rewrite a lot. My process is not very economical, and as a result I move slower than I would like, but at the end, I feel like I have done my best to imagine a full range of possibilities for whatever story it is that I am trying to tell.

Q. The writing process itself often teaches the writer something along the way. What did you take away from the experience of writing "Girls I Know"?

A. I think I have a sense now, a greater sense, that setbacks in the course of writing a book like this are ultimately beneficial. That having to rethink characters and situations ends up improving the final result, even if such a process is maddening and - at times - despair-inducing. I would say that I trust my instincts more now than I did before this book. I feel that I learned from the characters who populate this book, and that they provide something of a snapshot of America in the winter of 2001.

Jenn McKee is an entertainment reporter for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at jennmckee@annarbor.com or 734-623-2546, and follow her on Twitter @jennmckee.