U-M Institute for the Humanities installation toys with university history

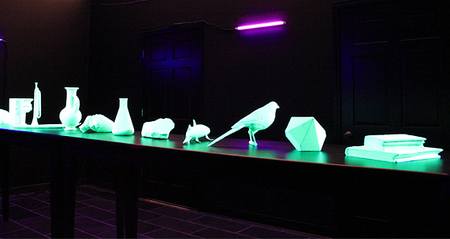

A detail from Dion's installation.

Just stay calm and take a seat. This exhibit goes from here to there and back again.

The gallery-sized installation by New York City-based artist Mark Dion toys with the U-M’s past through the guise of art. It puts all of aesthetics, history, and a decidedly unique logic of classification simultaneously into play.

As Institute for the Humanities Arts Curator Amanda Krugliak tells us in her gallery statement, Dion’s point of departure is “Michigan Chief Justice Augustus Woodward’s territorial act of 1817, establishing a ‘Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania.’

“Woodward harbored a dream of classifying all human knowledge,” says Krugliak, “and (he) had discussed this with his friend and mentor Thomas Jefferson. His plan would remain a blueprint for the university well into the 1830s, eventually replaced by a German model of education more in line with the U-M we know today.”

At this juncture of aspiration and evidence, Dion gets fanciful. This year’s U-M Institute for the Humanities Paula and Edwin Sidman Fellow in the Arts, Dion has made a career out of creating installations that reflect historical incidents and whimsical circumstance. His most recent commissions include a “Ship in a Bottle” public commission for the Port of Los Angeles and “Oceanomania” for the Institute Oceanographique de Paris et le Musee, Monaco.

As Clarrie Wallis, Curator of Contemporary Art at London’s Tate Modern Museum, has said of Dion’s 1999 “Tate Thames Dig” installation, “Like a good detective, Dion revels in seeing beyond individual fragments to recognize larger patterns; making connections between often seemingly unrelated objects and events.

“Dion creates new layers of meaning, linking our thoughts to the constructions of the past and choices for the future. True to the idea that the proper study of mankind is man, Dion leads us through the byways of natural history and comparative anatomy to bring us back time and time again to see ourselves, illuminated by this new and deeper knowledge, and to reassess our position within the current order of things.”

Likewise, Dion has said a little more succinctly of his work, “The job of the artist is to go against the grain of dominant culture to challenge perception and convention.” He certainly does this at the Institute for the Humanities.

By adopting methods of collecting, ordering, and exhibiting objects, he cleverly crafts installations that touch the border of scientific method and humanistic interpretation. And there are plenty of both science and humanism in his look at Woodward’s dream of Michigan’s intellectual future.

For this site-specific U-M installation, Dion took Woodward’s handwritten list outlining 13 different professorships for 13 separate academic disciplines, and he invented 13 visual symbols crafted through the U-M Duderstadt Center’s high-tech three-dimensional rapid imaging technology laboratory to illustrate each category.

These professorships—or “diadaxiim,” as Woodward labeled them— each tracks what Krugliak calls “an idiosyncratic system of classifications.”

Krugliak continues, “He invented outlandish words for these, mixing Greek and Latin, resulting in alliterative designations such as Anthropoglossica (Literature), Physiosophica (Natural Philosophy), Iatrica (Medicine), and Polemitactica (Military Science).”

As Krugliak tells us, Dion “imagined what objects would best represent these classifications and set out to find them in the many departments and collections within the university.” This would be no small task, and the results are what she good-naturedly calls “as much an expedition as a scavenger hunt, in part Aristotle as well as Don Quixote.”

Krugliak’s Aristotle/Quixote comparison is remarkably apt. Half the exhibition space has been draped in wall-to-wall black with three horizontal blue fluorescent lights attached at each of three interior corners. The 13 two-foot plaster figurines that Dion “found” (magpie, meteorite, flask, a bugle, heart, etc.; each representing one of Woodward’s arcane academic classification) sit in a row on a table dimly reflecting the blue light.

The space is eerie. The setting is eerie. The context is eerie.

As such, this half of the installation alone would be a peculiarly participatory work of art. But Dion also after bigger game: We must join in for his installation to work.

“First,” says Krugliak, “visitors to the gallery take a number, are seated in a waiting room, a carbon copy in itself. It is the familiar experience encountered in every institution, at the dentist’s office, or the DMV (department of motor vehicles). We are waiting, just waiting…for something extraordinary…to happen, transform us, alleviate the banality.”

And all banality aside, something will happen. Just don’t expect any sympathy from the receptionist. She’ll tell you she’s only there working nine to five. The waiting room has magazines to peruse and it has three clocks on the wall reflecting Istanbul, Paris, and Tree Town time.

The receptionist is brisk enough; the antechamber is generic enough; and the delay is just long enough to make us want something to happen. The wonder of Dion’s masterwork is that it then does what it says it will do. You just have to wait for the extraordinary.

“Waiting on the Extraordinary” will continue through Nov. 5 at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities’ Exhibition Space, Room 1010, 202 S. Thayer St. Gallery hours are 9 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday-Friday. For information, call 734-936-3518.