University of Michigan's Clements Library displays bygone representations of 'Murder Most Foul'

“Murder Most Foul: Homicide in Early America” at the University of Michigan William L. Clements Library proves that crime may not pay—but it always sells.

This expansive display of aged pamphlets, posters, drawings, broadsheets, newspapers, magazines, and books at U-M’s venerable library of Americana is unyielding in its pursuit of murder in the first degree. Indeed, the exhibit expands well beyond the traditional 16 display cases that have previously housed Clements exhibits.

It's certainly gallery space well spent. As Clements Director Kevin Graffagnino (who curated the show) told The University Record, “We probably have in this exhibit 15 different kinds of murder. We’ve got decapitations, hangings, dismemberments, stranglers, ax murderers, pistoleros, and other shootings with all manner of firearms.”

But Graffagnino’s even being a bit modest (or circumspect) about the exhibit's expansiveness, because there’s also a remarkable amount of mayhem here that includes gassings, poisonings, riots, and torchings.

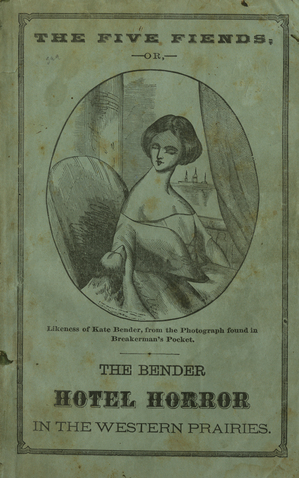

The cover of the pamphlet “The Five Fiends," from 1872-73

And this is uniquely possible to trace because of the Clements’ access to and consolidation of these sorts of materials. As the library’s exhibit statement tells us, the majority of the items on display come from its James Vincent Medler collection. Medler (1915-1997) was a Brooklyn, NY printer and lithographer “whose passion for three decades was collecting primary sources on early American crime.” The Clements Library’s 1992 purchase of the Medler collection “significantly strengthened” the library’s holding in this field.

Artifacts, however, need context, and the exhibit is ably supported by Thomas M. McDade’s 1961 “The Annals of Murder.” McDade’s day job through his lengthy career (as an attorney, an FBI agent, a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, and director of corporate security for General Foods) was supplemented by his equally ceaseless study of “the field of early American murder.”

His “The Annals of Murder” is considered “one of the finest genre bibliographies in American book collecting” and it stands a half-century after its publication as “one of the finest genre bibliographies in American book collecting.” So much so, “McDade’s annotations in ‘Annals’ are the source of most of the labels in this exhibit.”

The earliest artifacts on display are broadsheets whose graphics are relatively primitive. The writing is stilted, with an emphasis on the social element of the crime. Yet by the time the exhibit concludes, there’s a complete journalistic universe (perhaps best represented by the sensationalistic National Police Gazette) whose coverage was meant to titillate as much as inform.

There’s an equally interesting transition in the sort of crimes covered in the exhibit. Many of the earliest entries relate murders and crimes of resentment in either economic or social circumstances, while later entries focus on dramatic elements (patricide, matricide, or relationships gone bad) whose popular appeal are what Graffagnino described to Brown as “danger, excitement, impulses, and people we’re afraid of—and thus intrigued by.”

As just a few entries illustrate, the passions roiled by these horrific crimes are quite startling centuries later. Consider, for example, the case of “the Five (Bender) Fiends” or as the pamphlet on display relating their homicides phrases it: “the Bender Hotel Horror of the Southwestern Prairies.”

McDade’s annotation outlines this family who (as the exhibit's gallery tag says) “murdered about a dozen people near Cherryvale, Labetter County, Kansas in 1872-73. Operating a kind of rural inn, they murdered travelers for their money and buried them in the orchard.

“The Benders fled when suspicions were aroused, and a search of the farm revealed eleven bodies.” They were supposedly never captured; although as the display reassures us, “the behavior of one of the searching parties gave rise to the suspicion that they found the Benders and dealt with them summarily on the spot.”

On the other hand, we do know the famed 1893 “Devil in the White City” during Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition was eventually captured and executed. The subject of a relatively recent best-seller, this twisted tale of blood-curdling homicide revolved around another hotel. This one supposedly meant to house visitors to the world fair.

Instead, the structure created by Herman W. Mudgett (or “H. H. Holmes” as he was known in Chicago) housed an intricate “hodgepodge of rooms, passageways, concealed staircases, false walls, ceilings and chutes, with apparatus of a most sinister nature, including what was undoubtedly a gas chamber for the extermination of his victims.”

And what would an examination of early American homicide be without note of the infamous “forty-one” whacks of Lizzie Borden? The Clements includes her story by illustrating her famous Boston courtroom fainting through a classic drawing taken from the June 24, 1883 National Police Gazette.

Prominently set in this particular glass case is also a conveniently-sized hand ax. And poetic justice or not—for Borden was, after all, acquitted of the murders of her stepmother and father—it’s a final reminder that murder, while most certainly foul, is also of perennially sharp interest.

“Murder Most Foul: Homicide in Early America” will continue through Oct. 5 at the University of Michigan William L. Clements Library, 909 S. University St. Exhibit hours are 1-4:45 p.m., Monday-Friday. For information, call 734-764-2347.