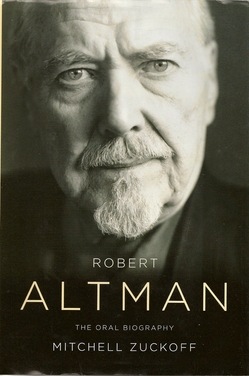

Robert Altman book explores life and times in overlapping dialogue

That’s not to detract in the least from the content in this massive tome, which begins with the emigration of the legendary director’s great-grandfather from Germany in the mid-1800s, and ends with what one of his sons called “an Altmanesque moment — four grown men in their underwear and shirts on the beach with ashes of their dad.” Along the way, Zuckoff covers almost every one of Altman’s credits in film, television, theater and opera, from his start making industrial training films in Kansas City to “Bonanza” to “M*A*S*H” to “Pret-a-Porter” to “A Prairie Home Companion,” at least in passing and sometimes in great detail. We're also let into his relationships with his kids, wives, siblings, actors, producers, and Hollywood “suits.” (And, of course, a bit of time spent in Ann Arbor.) And it’s all done in dialogue, culled from interviews with a couple hundred of Altman’s friends and colleagues and sewn together into a roughly chronological pastiche whose “story” is secondary to its genuine feeling of place — just the way, one hopes, Bob Altman would have liked it.

“I wish I could say that was completely my idea,” said Zuckoff by phone from Boston, where his day job is teaching journalism at Boston University. But really it was more a case of making the proverbial lemonade: Zuckoff had been interviewing Altman for a memoir about the art and craft of filmmaking, which was unfinished at the time of the director’s death in 2006. No one wanted to see this icon’s final, sustained interviews consigned to the recycling bin of history, so a group that included agents, editors, Altman’s widow Kathryn (more on her later) and Zuckoff got together and decided to write a different story, one that would use the transcripts as a backbone but bloom past filmmaking to include the life Altman dedicated to it, too. Zuckoff doesn’t remember who suggested putting it in the oral history format, “but as soon as it was said, it was like, ‘Oh. That’s what we have to do.’”

It’s executed masterfully. The cast of characters feels unwieldy at first, but their quotations are so well selected and tightly woven that it takes no time at all to let go and just read the story, realizing that important names will come up again and again until they’re familiar. People remember the same stories differently, and Zuckoff simply sets the contradictions next to each other for the reader to take in. Sometimes several dozen people say pretty much the same thing, which string together throughout the book to form a clear picture of a few unwavering cornerstones. The result is a strange and delightful meta-experience, in which the reader feels like she is learning about the ways Altman shaped our current sensibilities about art through his use of overlapping dialogue, improvisation and casting, while at the same time experiencing those elements firsthand.

Actually, by the end, the wealth of spot-on quotations led me to wonder uneasily about the quantity of material Zuckoff must have waded through to get 500 solid pages of the good stuff. “Oh, it was hell,” he said matter-of-factly. “It was horrible. I’m sitting in my office looking at the boxes and boxes of transcripts and materials that will have to be put in storage. I remember thinking, hey if they let me write a 200,000, maybe 500,000 page book, that would be fine. Then I’ll be able to cover all this.” He laughed. “I sort of compare it to good cooking, to reducing a sauce: You keep simmering off everything that isn’t the most flavorful, the most intense, that doesn’t have the most important elements. Anything that doesn’t satisfy those rules, even if I enjoyed it or liked it, went.” How long did it take? “It took 20 years off my life. Oh, that’s not what you mean? Actually, the whole process was probably about two and a half years.”

The picture that emerges is of an explosively talented man with a wide anti-authoritarian streak who is singularly driven to make movies. His tenderness with actors and artists (to a person, he commanded the respect of everyone from Warren Beatty to Cher to Meryl Streep to Lauren Bacall) was matched only by his insolence toward the management (he blew an early TV gig with Kraft Suspense Theater by saying their stories were as bland as their cheese, and later publicly wished United Artists studio head David Picker dead). Although he was perpetually on the edge of broke and ceaselessly shaking the trees for financing, neither his movies nor his parties suffered for it. His filmmaking was a family affair that encompassed his siblings, in-laws and children, but he proclaimed unabashedly that if he were forced to choose between film and family, he’d be sad as he waved his wife and kids goodbye.

The last statement jarred Zuckoff, who did much of his research after Altman’s death. “I knew Bob at the end of his life, and he’d mellowed quite a bit. He’d really had a third act in his life, so that was the man I got to know. But by going back into his life, I saw all these different Bob Altmans — and each one, they all sort of fit together; they all made sense, but they were all different. Some of the harder things (surprised me), frankly, like his relationship with his first wives and his earliest relationships with his children. I was at his house in Malibu and he was having a planning meeting and one of the people there was his son Steve (who worked as a production designer on a dozen Altman films). The meeting was over and Steve gave him a kiss goodbye. We’re talking about a 50-year-old man and 80-year-old man kissing goodbye, and that was sweet. And then to learn later that by his own admission he was not a good father was surprising.”

It doesn’t take even a shred of genius to realize that the person who made that transition possible was Altman’s third wife, Kathryn Reed Altman. Quoted extensively, she radiates through the book like someone you’re just sure you’d like to know. Steady enough to raise a passel of “hers, his and theirs” kids mostly by herself and fun enough to eat pot brownies in the front row at the Oscars, there is never an unkind word said about her by anyone. Even Zuckoff’s voice audibly brightens when I ask about the week and a half they spent traveling together to promote the book, including a November stop at the University of Michigan. “She is the greatest. When you asked about surprises, I should have answered how much I would fall in love with Kathryn. She’s delightful and fun and witty. She’s a party. She’s a blast.” Not words often said about a woman who married her second husband half a century ago, but Zuckoff backed it up: “Literally, I’m a relatively young guy, and we had an event in Kansas City, and it was like 10 at night when we got done, so I’m thinking — maybe it’s even 11 — we’re going to go back to our hotel because we’ve got an early flight to Michigan the next day. And she’s like, ‘What are you talking about? We’re going to go see what’s open!’ And then we’re just pounding red wine…”

Their visit to Ann Arbor was partly to pay tribute to the director’s history with the University of Michigan. Film studies professor and WUOM film reviewer Frank Beaver recounts that Altman was invited to direct a 1982 School of Music production of Stravinsky’s opera “The Rake’s Progress,” simultaneously teaching a class about his films with Beaver in what became a semester-long fellowship. Altman returned two years later to film a one-man, one-set play about Richard Nixon’s mea culpa in Martha Cook Residence Hall, which became the critically-acclaimed “Secret Honor.”

He was given an honorary doctorate in 1996, the only one he has as far as Zuckoff knows, and the university offered the winning bid in an auction of Altman’s records and memorabilia earlier this year.

“He really loved his time there,” commented Zuckoff. “It was very important to him, coming as it did at a time when he was not on top of the world. And then there he was, sitting next to Sandra Day O’Connor and getting his doctorate. Here was a guy that was as smart as anybody, but he didn’t go to college, and I think (that degree) meant a lot to him.”

In a quote taken from an interview with his publisher, Zuckoff said, “I don’t think it’d be remotely possible for a director like Bob Altman to operate in today’s Hollywood.” And the explanation he went on to give, that Altman’s disdain for “the suits” and knack for ticking them off would sink him so fast in today’s atmosphere of concentrated power, money and control that he’d never have a chance to be heard, made a lot of sense in a tragic sort of way. Is originality in Hollywood just lost forever? “I’m an optimist by nature,“ he told me. “I feel like Hollywood has changed, from the seventies and through the eighties and nineties, so I’m hopeful that it will change again, that we’ll recognize that the artists really are the key to Hollywood. And I think there will be another golden age — it’s just a matter of when. Unfortunately now, the safety approach — they’ll let you go out and make a Poltergeist or something, but it can only cost a million dollars. And sometimes it costs more to make great art. Someday, we’ll have to take a risk.”

New to Robert Altman? I asked Zuckoff to offer a few recommendations suitable for a little introductory film festival. “Oh, man, this is like making a playlist for your girlfriend. Hmmm… I feel like you can’t get the feel of him unless you’ve seen “M*A*S*H,” “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” “Nashville,” “Short Cuts” …and maybe “The Player,” but I’m going to say “Gosford Park.” BUT, if you want sort of the unseen Altman, the overlooked Altman if you will, I’d say “Brewster McCloud,” “Buffalo Bill,” “Popeye,” “Cookie’s Fortune” and “The Company.” He never made the same film twice, and even the ones that are not commercial successes are unique in their own way.”

You can get a copy of “Robert Altman: The Oral Biography” at Borders, Amazon and Knopf.

Leah DuMouchel is a free-lance writer for AnnArbor.com.