New Yorker staff writer, and University of Michigan grad, Susan Orlean recalls life in Ann Arbor, early career

Q. After growing up in Cleveland, what attracted you to the University of Michigan?

A. First of all, I knew so many people here. I think because I was in Cleveland, (Ann Arbor) seemed like this wonderful, but not-so-remote, … essential college campus town. … I visited a bunch of schools that I had thought I’d really want to go to, and I really just didn’t feel comfortable. I think my Midwesternness was so profound that seeing schools in the East—I just found them uncomfortable and alienating. And then I came to Ann Arbor, and I just said, "This is it. This is where I want to be." I just loved the feel of it. And the familiarity. It was sort of like a dream version of where I’d grown up, just because it felt familiar, but then was also marvelously populated by thousands and thousands of 18-year-olds.

Q. The bio on your website describes your time at U-M as "happy but relatively squandered." Could you expand on that?

A. I think college is usually wasted on college students. What is happening for you, in those years of your life, if you’re anything like I was, is that you’re growing up. … What preoccupied me was: living on my own for the first time, falling in love, and being part of the whole atmosphere of being in college. And only when I went back to college as a Nieman Fellow (at Harvard), which sends you back to college for a year as a grown-up, did I think, "Oh my God, there was this amazing opportunity to just go to school and learn things and read." And I think when you’re that young, you’re preoccupied both with the idea of growing up but also, your concerns are so specific, which is: what should I major in, and what am I going to do when I get out of college? It’s harder then to simply enjoy education for its own merits. So that’s really what I mean.

Q. What are your fondest memories of your time in Ann Arbor?

A. Sitting at Dominick’s after class, talking. It’s such a vivid memory. I was an English major, and the English department was fantastic. As much as I’m saying I squandered my time, I learned a huge amount, and took great classes, so I’m exaggerating a little about the squandered nature of it. But I loved being in Ann Arbor. I loved the experience of being part of this living, breathing organism of college students. Just that feeling that people were doing interesting things everywhere you looked. But I have the strongest memory of sitting around after class at Dominick’s—they have sangria, right? And an incredibly good tuna sandwich— and just talking about class, talking about what we were reading—it was just a very happy memory.

Q. Did you do any writing for The Michigan Daily?

A. I hung around with a lot of people who were on the Daily, but I only wrote a book review for the Daily. I knew even then that I didn’t want to be a daily newspaper writer. And everything about the Daily, the seriousness of it, was about being a newspaper reporter. So even though I think it would have been a great exercise for me, I just kept thinking, "Well, no, what I really want to do is write for the New Yorker." And in my great naive college student way, I thought, "Well, I’ll just wait for that opportunity."

Q. It sounds like The New Yorker was on your radar from a young age. Did you grow up with it around the house?

A. It was given to me as a Christmas present by a friend of mine in Ann Arbor. When I first started getting it, it was when I was in college, and it was being delivered to me at East Jefferson Street, in my funky apartment, and it was just a revelation. It was suddenly as if the kind of writing I most wanted to do materialized in front of me, and I thought, "Hey, you can really do this. There really is a place that runs these kinds of stories." Because I didn’t grow up reading it. I grew up reading Time and Newsweek and Life, not The New Yorker.

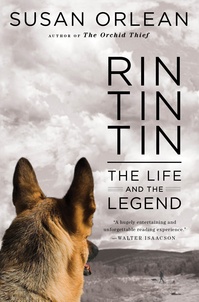

Q. You studied English and history during your time at U-M. Were you hoping to do work that would combine the two things—as "Rin Tin Tin" clearly does—or were those just your biggest interests at that time of your life?

A. I am really interested in history, and I feel that to tell a story well, often, there are many layers, and many of those layers are often temporal layers. You want to go back and see, how did we get to this point? So I think it’s an instinct rather than a deliberate decision. When I started working on "Rin Tin Tin," I was a little intimidated by the scope of the historical research that I was going to have to do. I thought, "Boy, I’m not a historian. I don’t really know how to do this. But I’m a pretty good reporter, so maybe I’ll just think of it the same way." And the fact is, it’s not very different. That investigation is rather similar, and I think that I got more and more comfortable as I was going along, realizing that you could make a story in which all the primary characters were not alive. You could tell it with the same energy that you told a story that was happening in real time. It required a kind of leap of confidence to do that.

Q. After graduating from U-M, you went to Portland, Oregon, where your writing career began. What took you to that part of the country?

A. I had a very, very sophisticated reason for going to Portland, which was, my boyfriend was moving there. And like so many life decisions, it was based purely on impulse. … I was stalling for a year before what seemed to be looming ahead of me—namely, law school. Not that I wanted to go, but it seemed like the only viable option for an English major. So I went out to Portland expecting to be a paralegal. I mean, that’s what I imagined. I’d get a job as a paralegal, and that would prepare me for law school. I never dreamed that I would get a writing job, because I had no idea how you got a writing job, and I had no experience. So it was pure luck that there was a little magazine starting up. Experience seemed to be less important to them than passion, which I had by the bucketload. And the minute I heard about this job, I just thought, "You have to give me this job." I mean, I practically fell on floor pleading, saying, "You have to hire me. I have to do this. I want to do it so badly." And whether to humor me or just because the show of devotion was so impressive, one way or the other, I got the job, and then I never looked back.

Q. Do you propose most of the story ideas that you pursue for The New Yorker at this point? And do stories sometimes not pan out?

A. I would say 99 percent of the time, they’re my ideas. … And that’s an important part of the job, I think, is finding good stories. … Usually, if early on, I start getting this sinking feeling that there’s less there than I’d hoped, I’ll bail out quickly. But I think by the time I settle on an idea, I’m usually pretty committed to it and pretty convinced that there’s a story to tell, even if initially it’s kind of hard to get it to shake loose.

Q. Given the vast scope of a book like "Rin Tin Tin," how did you keep from getting lost in the research?

A. The truth of it is, the only way that that can really happen is having a deadline, because … you could research a story with this amount of history forever. So it’s a combination both of … a publisher waiting and saying, "I thought you said you were going to be done?" And secondly, I think there’s a gut instinct that you have, and you hope to develop, which says to you that you know enough now to tell a really good story. Not that you know everything, not that there isn’t more to learn, but that you’ve plateaued, and you’ve reached a point where the story makes sense to you, and you can tell it. … I worked for a long time at The New Yorker when we didn’t have deadlines. And for some people, that was absolutely torture. They found it impossible to ever finish a story. And I think I always had a certain amount of discipline and also eagerness to say, "I’m really excited. I just found this amazing, cool story that I want to tell you." So my impatience to tell the story helps motivate me to finish. Also, knowing that I wasn’t trying to give the definitive, ultimate answer to anything as much as saying, "Oh, I just learned the most interesting thing." … So I think those two things worked in my favor: a kind of natural urgency on my part, an excitement to tell, and then, having come up in my career when there weren’t deadlines, so I had to teach myself that kind of discipline.

Q. Something I've always appreciated about your writing is that often, even though I don't initially think I'm interested in the topic, I'll read the first paragraph, and then a few more, and I end up being sucked into reading the whole article.

A. I think I have a little bit of a thrill-seeking urge, which is to say, I’m going to write a story about something that I know probably no one is going to want to read, but I swear, I’m so excited about it, I just know they’ll get excited. But that’s not always endeared me to editors, because —I remember when I went into my publisher and said, I want to do a book about this weird guy who got caught selling orchids, and you see their face fall. And you think, OK, I know that sounds weird, but it’s a great story! I’m serious! And I think that there’s an incredible pleasure in telling a story that you know people come to with a bit of skepticism. And so there’s a seduction involved in saying, no, no, really, stay for one more sentence. Stay for one more. Stay for one more.

Q. Magazines are struggling mightily these days, and venues for the kind of work you do seem to be drying up. As someone who primarily writes long, in-depth magazine articles, what do you think the future holds for your chosen form?

A. We’re in a really interesting period, and I think that the Internet is actually going to be very liberating, because the cost of making stories available will be much less of an issue. And I think it will make it possible to not have every story have to be … something commercial and instantly recognizable and marketable. That’s my optimistic view. I think magazines will probably migrate more and more to being on the Web. And while I don’t love that, I think the best thing about it will be that length of stories won’t be as much of an issue, and real estate won’t be as much of an issue. That you can run stories that are a bit off-topic - it will just make that so much easier to do. So I’m hopeful. I think we’re in the middle of a huge amount of change, and it’s going to keep changing. But I think a lot of the changes are going to be beneficial. … I think it will make it easier to be a little more adventurous with what we write about.

Jenn McKee is the entertainment digital journalist for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at jennmckee@annarbor.com or 734-623-2546, and follow her on Twitter @jennmckee.