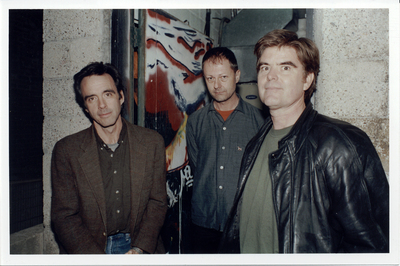

Reunited Mission of Burma playing the Blind Pig

Eight years in, the Mission of Burma reunion seems to be going well for guitarist / singer Roger Miller (an Ann Arbor native) and his Burma bandmates.

Art-punk giants Mission of Burma take the Blind Pig stage on Thursday.

photo by Diane Bergamasco

The group initially released three albums worth of pioneering, brainy-but-cacophonous art-punk between 1979 and 1982 — and then broke up in ’83. But the split wasn’t for any of the usual break-up reasons: there were no personality clashes, no drug problems, no creative differences. Instead, it was because Miller was afflicted with serious tinnitus. So, he quit playing high-decibel punk rock “because I decided I still wanted to be able to hear when I was 50 years old,” he says.

So, the group members went their separate ways, with Miller forming the Alloy Orchestra, a lower-volume ensemble that features Miller on keyboards and which performs scores for silent movies. (Alloy has performed at many silent-film screenings in Ann Arbor and Detroit over the years.)

But the Burma stars again aligned, loosely, in 2002, when three of the four original members got back together for what “was supposed to be just two shows, one in Boston and then one in New York,” says Miller, who joins his Burma bandmates at the Blind Pig on Thursday.

“Then it sort of snowballed and took on a life of its own. None of us are career-oriented — we didn’t really have a plan. But we enjoyed playing Mission of Burma music again, and decided, ‘OK, let’s each write a new song,’ and then that led to several new songs” — which led to an album, which led to two more albums, and many tours, and now the band finds itself eight years into its second life.

As for the tinnitus, “I still have it, but by taking so many years off from making really loud punk music, I have attained my goal of still being able to hear after the age of 50,” says Miller, now 58, with a laugh. “Plus, Mission of Burma, as an energy form, is just too interesting not to do it.”

PREVIEW |

“Like, I don’t use a monitor onstage, and I wear super-heavy-duty ear plugs, and I have my amp off to the side instead of right behind me,” says Miller during a phone interview from his home in Boston. “Plus, we put a plexiglass wall between Peter’s kit and me.” (That’s Peter Prescott, the band’s drummer, who, after Burma’s ‘80s split, formed another band, the Volcano Suns.)

Of course, rock’s most famous tinnitus sufferer is Pete Townsend, who took similar precautions for a few years — standing inside a plexiglass “booth” for one late-‘80s tour, then playing only acoustic guitar for the 1996 Quadrophenia tour. But in 1997, Townsend strapped on the Stratocaster again, and ever since, he’s played blistering electric guitar whenever the Who has toured. But, recently, Townsend said the tinnitus has become more severe again, and said the Who may have to stop touring completely at this point

“Townsend, and the Who in general, played a lot louder, and for a lot longer, than we did,” says Miller, explaining the difference between his situation and Townsend’s. “But it’s not something that comes and goes, not for me, anyway.”

Burma’s latest album, “The Sound The Speed The Light” captures many of the elements of the band’s first go-round — the slash-and-burn guitars, the whomping, tribal drums, the sometimes-intricate riffs and rhythm patterns and the arty tape-loop effects. And some of the music still recalls that of Wire, a similarly-arty punk band that was one of Miller’s biggest inspirations. And many of the lyrics still tend to be cerebral — also a Burma hallmark back in the day, and which conjures the Wire influence as well.

Listen to the Mission of Burma album “The Sound The Speed The Light”:

“Wire had the real essence of punk — tight, stripped-down, but with that intellectual overlay — but they're more formal than we are. They’re very structured, while we’re more chaotic. But, like Wire, I’d say that we ‘think’ more than the average punk band.”

For the latest album, Miller says he wanted the music to be “more spacious” than the music on the group’s previous disc, “The Obliterati,” which delivered an even more aggressive sonic attack. “But then, ‘Obliterati’ also had string arrangements, which we love, but this time we added more keyboards.

“We’re pretty un-self-conscious about what we do. We just set up, and play music, then later figure out what it was we did. Our music is pretty distinctive music, I think. When we got back together, Pete (Prescott), who’d kept playing rock music all those years, said that he immediately began writing differently — he began writing ‘Burma songs.’ But, still, I think there’s a lot of leeway and diversity within our music — we can go from compressed punk to some sprawling psychedelic miasma kind of thing.”

Miller has two brothers who are also musicians. One, Laurence, still lives in Ann Arbor and creates eccentric, unique children’s music (and also teaches music) under the moniker Mister Laurence. Another brother, Benjamin, lives in New Jersey and often plays with Roger in an ensemble they’ve dubbed M2. “And when Laurence joins in with us, that’s when it becomes M3.”

Back in 1969-1970, while Miller was still in high school, the brothers were in a local psychedelic band, Sproton Layer, that also featured Harold Kirchen (brother of Bill Kirchen ) on trumpet. They recorded an album, "With Magnetic Fields Disrupted"-- but it was never released until 1992, on the New Alliance label.

Says Miller with a laugh: “It was ‘the great lost psychedelic record.’”

Kevin Ransom is a free-lance writer who covers music for AnnArbor.com. He can be reached at KevinRansom10@aol.com.