Shedding light on kitchen culture behind bars

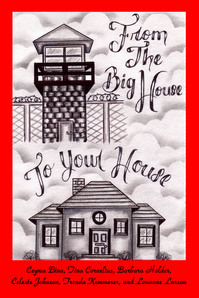

In this book cover image released by The Justice Institute, "From the Big House to Your House," a collection of 200 recipes by six Texas prison inmates, is shown.

AP Photo | The Justice Institute

GATESVILLE, Texas (AP) — These women may not have an oven, refrigerator, stove, knife, or even the ability to boil water, but they do have plenty of time on their hands.

Decades, in fact. And that, combined with a few (admittedly peculiar) ingredients and a desire to cook despite the odds has resulted in a rather unusual cookbook — "From The Big House to Your House," a collection of 200 recipes by six Texas prison inmates.

The women all are serving at least 50 years at the Mountain View Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, all but one of them for murder. And a hankering for foods they enjoyed on the outside prompted them to get creative on the inside.

For example, they've found that an empty potato chip bag works for cooking in a quart-size electric warming pot, their only source of heat for cooking. A plastic ID card — similar to a credit card — makes an acceptable cutting or chopping implement. And tuna and mackerel can be made into great-tasting nachos.

"I know it sounds disgusting," said Celeste Johnson, 49, one of the authors. "But I love tuna nachos. And I've got so many people here converted to it."

The book was produced with the help of Johnson's mother, who typed the recipes and submitted the manuscript on the women's behalf to The Justice Institute, a Seattle group that works with convicts who maintain their innocence. The group published the book and now sells it online.

The book puts into print a long tradition of the joy of cooking behind bars, where generations of Martha Stewart wannabes have concocted legal and illegal brews and stews with a variety of success and failure.

And inmate cooking is not confined to women's prisons. Former Texas corrections officer Jim Willett remembers his days working in a men's unit, walking through a cell block and getting whiffs of simmering foods.

Ceyma Bina talks from behind the glass in the visitors area of the Mountain View Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice Tuesday, Jan. 10, 2012, in Gatesville, Texas. Bina is one of six women convicts, all with sentences in excess of 50 years, who have written and published a cookbook of recipes using items available in the prison commissary.

AP Photo | Pat Sullivan

"Something like a Frito pie they're certainly not going to get in the chow hall."

The reality of prison cooking is a bit different from "GoodFellas," the 1990 movie that shows mobsters delicately slicing garlic with a razor blade as they prepare a gourmet Italian dinner for themselves while serving time. And it isn't always pretty.

Inmates tend to be creative in the "kitchen." In the past, some have been known to fashion metal plates into skillets that get heated in toilets filled with burning toilet paper. Or to transform tooth paste tubes into spoons and turn fruit into prison "wine."

In 2009, a Washington state prison inmate's attempt to warm sausages in his cell's stainless steel commode didn't work as hoped. Smoke from the prisoner's makeshift oven went through a sewer pipe vent and officials evacuated the lockup for what they feared was a fire. The inmate became known as the "toilet chef."

More typical was the experience of Martha Stewart, the homemaking pro who was said to have dabbled in microwave cooking while locked up a few years ago in a federal prison in West Virginia while serving time for obstruction of justice and lying to the government.

At least she had a microwave, which Federal Bureau of Prisons spokesman Chris Burke said is available to many federal inmates, though they are prohibited from cooking in their cells.

The Texas women — who, in compliance with regulations prohibiting them from profiting from a business while behind bars, are donating proceeds from the book to their publisher — only have their "hot pot," a coffee pot-like instrument that warms water, but can't boil it (boiled liquid could become a weapon).

Ingredients also are limited mostly to what can be purchased from the prison commissary. They can forget about real milk — they get powder — or real butter, as well as most individual seasonings. Garlic? They squeeze that from garlic vitamin tablets.

"It looks kind of gross," Johnson says. "But it works. You'd be surprised."

Looking for alternatives to meals served in the chow hall, the Texas women began pooling their commissary food purchases and wrote down their discoveries, such as rehydrating potato chips in their warming pot. The resulting mush became a "baked potato."

"I don't know if we've been away too long, but it does taste like a real baked potato," says Johnson, who's been in prison for nine years and won't become eligible for parole from her life sentence until 2042.

Prison historian Mitch Roth said cooking is a way for inmates to "access their former lives to a certain extent," and to humanize the often dehumanizing prison experience.

Not every recipe the Texas women tried was a winner. Ceyma Bina, one of the co-authors who has served six years of a 50-year sentence for a slaying in Houston, winced as she described making ravioli from ramen noodles and salsa. And Johnson said rehydrated onion-flavored potato chips "turned like rubber."

Bina and the others who worked on "From The Big House to Your House," say in the book's preface they were confident readers on the other side of the bars would "enjoy the liberty found in creating a home-felt comfort during unfortunate times."

"It shows people how we survive in here," said Bina.