Doug Stanton's 'Horse Soldiers' fight 21st century war on 19th century terrain

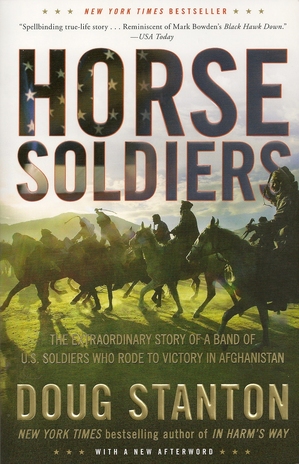

One is hardly finished reading the title of Traverse City writer Doug Stanton’s latest book, “Horse Soldiers: The Extraordinary Story of a Band of U.S. Soldiers Who Rode to Victory in Afghanistan” (Scribner) before the questions start. Wait, what soldiers? When did that happen? When did we win in Afghanistan, anyway? And if we already won, what are we still doing over there?

The war story Stanton tells is full of diabolical bad guys, mystery-shrouded good guys, geopolitical intrigue, exotic terrain, military pyrotechnics, deception, gallows humor and really long odds — in short, a magnificent classic. It’s also the true story of United States Army Special Forces Command Fifth Group, the first boots on the ground in Afghanistan after Sept. 11. It’s the first time we’ve ever led a war with this unit Stanton describes as a “secretive branch of independent warriors,” and that’s because they’re not like the regular Army:

“They fought guerrilla wars. This fighting was divided into phases: combat, diplomacy and nation-building. They were trained to make war and provide humanitarian aid after the body count. They were both soldier and diplomat. … They spoke the locals’ language and assiduously studied their customs concerning religion, sex, health and politics. … Special Forces thought first and shot last.”

The idea, by late September 2001, was to support the Afghan Northern Alliance soldiers, who had been fighting a losing war against the Taliban for years, by using American airpower to blast the enemy out of the country. The operation would be guided by Special Forces soldiers, whose job it was to get behind enemy lines to identify targets for bombing and ease long-held rivalries between the Northern Alliance warlords enough to consolidate their ground troops. In mid-October, a Nightstalker helicopter disgorged a dozen soldiers into the Darya Suf river valley to meet up with three CIA paramilitary agents at Afghan General Abdul Rashim Dostum’s base camp to accomplish this.

When the colorful and surprisingly endearing Dostum rode up with his men the next morning, he graciously accepted his gift of vodka before snapping out a far better map of the region than the Americans possessed and crisply detailing a battle plan. They would head north, securing more than 50 miles of river valley on the way to the town of Mazar-i-Sharif. If that fell to the Alliance forces, so would all six provinces in the north, followed by Kabul, then Kandahar, and finally the country. They would begin immediately, said Dostum, by traveling to his makeshift headquarters in the village of Cobaki. On horseback.

“The U.S. Army did not offer ‘Horsemanship 101’ as a matter of course,” writes Stanton dryly. “No one in Washington, D.C., had imagined that modern American soldiers would be riding horses to war.” So Captain Mitch Nelson put on a thirty-second crash course in making the animals go and stop, issued a sternly worded warning about using one’s pistol to avoid being dragged over rough ground and barked the Dari word for “giddyup” before following the general’s dust trail out of town, calling over his shoulder for his men to catch up. They were joined two weeks later by another Special Forces band riding with General Atta Mohammed Noor, all of them making a charge up the Darya Suf that Stanton describes with a journalist’s incision and a poet’s phrasing. (The otherworldly novelty of, say, a bank of solar cells transported by mule is just jarring enough to make a giggle escape.)

The mission went astonishingly well. In capturing Mazar-i-Sharif, Stanton says the soldiers “accomplished in two months what Pentagon planners had said would take two years. In all, about 350 Special Forces soldiers, 100 CIA officers, and 15,000 Afghan troops succeeded where the British in the nineteenth century, and the Soviets in the 1980s, had failed.” An army of 50,000-60,000 Taliban was defeated. It was all over but the nation-building.

This is where the story stops, and if it were fiction, I would have just committed the unpardonable sin of giving away the ending. But one of the most disconcerting things about reading this book is that, unlike accounts of skirmishes in which the ultimate victors have long been proclaimed by the somber voice of history, we still don't know how this is going to turn out. The open-endedness that hangs over the incongruity between the success we’ve just witnessed and today’s nightly news is particularly heartbreaking after the book's early pages transport us back to the minutes in which the horror of 9/11 was so fresh it scorched our souls.

The missing link, posits Stanton in the epilogue, is Iraq: as resources and personnel were funneled away from Afghanistan — a nation in need of serious building after decades of Soviet occupation followed by civil war — the Taliban regrouped into the spaces left behind. Worse, the Pentagon chose an altogether different strategy in 2003 when Ambassador Paul Bremer disbanded the Iraq National Army rather than working with it, sending a half a million armed and angry young men home to their bombed countryside. “We just lost Iraq,” an officer who had fought alongside Dostum told Stanton five months before the infamous Mission Accomplished banner flew.

What’s Afghanistan like now? Even though Stanton may be one of the best people around to ask, having returned from a follow-up visit just days before chatting with me by phone, his answer began with a pause. “Well, you’re just catching me trying to figure out what I found. The country is really trying to figure out a sense of governance. They’ve been at war for 31 years,” so the infrastructure that supports everything from getting a few things from the store to securing justice for capital crimes simply isn’t there. “The Taliban are driving around the country on motorcycles holding court,” explained Stanton matter-of-factly. They're arriving at cities and meting out justice from the center of town, multitasking at solving administrative issues while instilling fear in the citizens. “So the tradeoff for you and I if we were living there,” continued Stanton, is that we’d end up thinking “’I’m not in support of the Taliban, but I can’t live my life,’ with questions from ‘Do I own that piece of property?’ to ‘My brother was assaulted.’ So the Taliban apparently have a presence in 33 of the provinces. The sense of security is welcome, but the Taliban as an ideology are not.

“What is more complex today, after 8 years, is the back and forth between U.S. and international forces. Gains have been made, but the locals are wondering what’s next. Can the U.S. and Britain and other countries do anything about this? Back in 2001, that (thought) wasn’t there, because in six weeks they basically pushed the Taliban out of the country and collapsed their command structure. People were very happy. They’re still happy today; I didn’t find any seething resentment toward the American presence.” There is, however, what he calls a lingering “whatever we would feel if our house was bombed mistakenly. A confused, ‘I don’t like the way things are but I don’t know what else,’ ‘sometimes things blow up that shouldn’t’ feeling."

"And it’s confusing to us as well as them. The idea of ‘winning’ is very different for us than it was in 1945 when WWII ended, and (in) my trip last week, (it) was very different from ‘winning’ in 2001. Then, the goal was to make it unsafe for the Taliban. They had to go away, or get bombed, or surrender. But today, we think, ‘OK, maybe there will be Taliban.’ It’s clear that our job is not to occupy and conquer them. So maybe they’re here, but they’re no longer fighting. Maybe they’re in the government. In the south, in Kandehar, if you had a parliamentary government, you would have members of parliament who would be quote ‘Taliban,’ and they would still have a voice that Afghanistan needs to be governed by Sharia law.”

But mostly in his trip, Stanton said, he heard discussion about “what civilians are doing, both internationally and in Afghanistan, to create governance. So that if all this kinetic energy ends, and the room goes quiet and there’s nothing blowing up, you look and there’s this vacuum - no schools, no communities. What’s the civilian side doing to create peace and tranquility?”

When Stanton set out to find a new project during the long post-production period for his last book, “In Harm’s Way: The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis and the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors,” he had no idea that some of the best answers to that question were to be found in the military. He’d read a 2002 Time magazine article by correspondent Alex Perry (whom we meet frequently in “Horse Soldiers”) and wondered if he could approach modern soldiers and interview them in the same way he had World War II veterans. He found he could, and a year into his travels, he “realized that it was really a book about problem-solving. These guys, I didn’t know anything about this, but they were just as happy to change the way people thought” as they were using force. (Or, as ground commander Major Mark Mitchell put it, “Brains before bullets. Outthink ’em so you don’t have to outshoot ’em.”) “And after 9/11, there was the question of, ‘How do you solve the problem of violence in the world?’ Contrary to popular belief, I don’t think anyone likes war, but I do think there are people who like being in the middle of it and trying to figure out what to do next. It seemed surprising to me. It wasn’t my image of the army.”

Doug Stanton will read from "Horse Soldiers: The Extraordinary Story of a Band of U.S. Soldiers Who Rode to Victory in Afghantistan" at the downtown branch of the Ann Arbor District Library at 7 p.m. Monday. It may interest military history buffs to hear that he will be in Lansing on Tuesday for Michigan Author Homecoming discussion with Benjamin Bush and Philip Caputo called "Writing War: Afghanistan, Iraq, Vietnam" And literature fans may like to check out Stanton's year-round author festival in Traverse City called the National Writers Series, which will host Tom Brokaw, Mario Batali, Thomas Lynch and Woody Harrelson among others this year.

Leah DuMouchel is a freelance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.

Comments

Tom Collier

Sat, May 15, 2010 : 11:36 a.m.

Thanks to Ms DuMouchel for an excellent review. She correctly described Special Forces guys as quick thinking, adaptable, aware of the cultures of others, and good at what they do. The many Special Forces guys I have known would appreciate her comments. Stanton will be at the downtown A-A Library Mon, May 17, 7-8:30Pto discuss "Horse Soldiers."

Marge Biancke

Sat, May 15, 2010 : 9:13 a.m.

Mr Stanton will be speaking in Ann Arbor at the Margaret Waterman Alumnae Group luncheon in November