Winter days foster reflection: Essays on death in Ecotone literary journal just right for this time of year

The Ecotone Journal is published by The Publishing Laboratory and the Dept. of Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

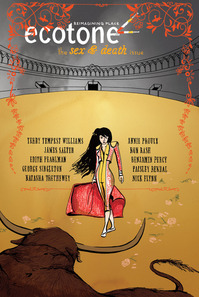

As the cold winter has landed, I've been keeping warm reading essays contemplating death, nature and serendipity. While I didn't intend that, upon reflection, it does seem most appropriate for this time of year. I picked up the most recent issue of Ecotone, a literary journal. In this, "the sex & death issue", I am intrigued by an Annie Proulx essay, A Yard of Cloth, and Jill Sisson Quinn's piece, Sign Here If You Exist.

Proulx tells of a fairly straightforward incident — she and her sister visit their mother over Thanksgiving, and, on the return trip home, they stop in a fabric shop. Then, once on the road, they come upon a car accident. Help is obtained, they return home, and soon the story is conveyed to their mother. But there is more (isn't there always?). The man in the fabric shop, who had so repelled Proulx, was in fact family, unknown to her at the time. She begins to think of the connections of people, her own roots and her sense of displacement — belonging to Franco-Americans, yet also embedded in her life of solitude.

Meanwhile, Quinn examines her view of God, afterlife, family and ichneumon wasps. The title of the piece comes from an incident from when she was a child. She once left a note to God indicating, "sign here if you exist". Soon thereafter, the note contained a response in her mother's handwriting so familiar to her — no forgery was involved, just a commentary on faith and belief.

For Quinn, whatever her views on God over her lifetime, she continues to cling to the idea of an afterlife — something that allows connection beyond this world. Enter the ichneumon wasp. The ichneumon is a parasite which kills its host to feed its larvae. The larvae are hidden deep in the wood of dead trees, a space she describes as "burrows that double as grave and womb." There is something in this ruthlessness that is deeply unsettling to Quinn's own views — well, wishes — in regards to death and what may be beyond.

As she writes of the relations between herself and her mom, relations that are finite if there is no afterlife, Quinn leaves the reader with more to contemplate rather than providing any self-defined answers. This could be said of the Proulx piece also, as I felt unease rather than gratified by the end.

Perhaps it is perverse of me, but as I look at the dead trees in my own backyard and communicate with my own long-distance family, I like that this is what I have been reading of late.

Julia Eussen received her B.A. in English from Kansas State University. She is currently a graduate student in Eastern Michigan University's Professional Writing Program. She is also an active member of the Ann Arbor Classics Book Group and has recently begun to re-acquaint herself with good poetry. She can be reached at jeussen at emich dot com.