Under Anne Sexton's pen, Grimm's Fairy Tales are 'Transformed'

I spent much of these past autumnal months reading the poetry of Anne Sexton.

After dissecting her work I find myself again in love with the first book I encountered of hers nearly twenty years ago - Transformations.

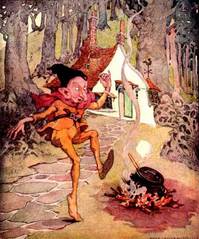

Rumplestiltskin image provided by Grandma's Graphics and came from Anne Anderson's Fairy Tales and Pictures. (Whitman Publishing Company, 1935.)

When I first pulled this book from the shelf, Anne Sexton was only a name, and I knew little of her life or writing style. I was ill-prepared for her versions of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, Rapunzel, Rumplestiltskin, Briar Rose and the other tales contained in this slim volume. I re-discovered the fantastical worlds where gold is spun nightly and also relished the images which through her looking glass are most wonderfully skewed.

Cinderella is a “regular Bobbsy twin,” Snow White a “dumb bunny,” and Briar Rose an insomniac. The tone of each poem is very different than what Walt Disney taught me as a child.

Sexton has a way of keeping them in today’s world. Some of them are simply amusing due to her flippant tone, others because she gives details which make them (almost) completely believable. For example, in “Hansel and Gretel,” I learn the sun was in the astrological sign of Leo when they first became lost. The opening verse of Cinderella tells me exactly what lays ahead: “You always read about it: the plumber with twelve children who wins the Irish Sweepstakes. From toilets to riches. That story.”

In this volume of poetry, what interests Sexton the most is deception. Essential to such tales - mistaken identity, a deceptively nice wolf with hunger pains, hidden liaisons and dubious talents - deception is not only for the tales, but for today’s world as well. The scenes may have changed slightly, but the elderly are still swindled of their savings (if not their grandchildren), and women still deceive themselves when looking in mirrors and questioning their beauty and age.

What unfolds in these poems is both the deception and a glimpse into the “why.” What motivated such an act to begin with? And, not always, but on occasion, this leads the reader to have some sympathy for those who are initially considered villains. I get a different view of Rumpelstiltskin or Rapunzel’s keeper.

Like any good book, what makes this a wonderful read is that when I least expect it, the poetic verse takes another turn and I am in a new world where the characters are not quite as familiar as I thought.