Ann Arbor Art Center exhibit explores potential of art on the edge

“Amarillo” by Dewey Blocksma

No problem. This exhilarating mixed-media display—featuring the art of Dewey Blocksma, Len Cowgill and Tim Burke—has lots of other things on display.

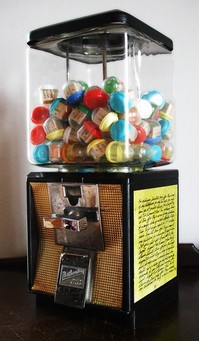

Included in the mix are slate and glass; a metal cream separator, pinball machine, and gumball machine; as well as color pencil, white charcoal, human teeth, piano keys, timber, deer jaws, wooden car molds, and some really old photographs.

The show contains three distinct varieties of outsider art. As the Art Center’s gallery statement pithily tells us, these 3 artists “challenge the role of formal art training” by “residing ‘outside’ the normal constraints of the traditional art establishment.”

But what happens when outside-the-establishment becomes the norm? This is the view at hand in “Everything and the Kitchen Sink.”

Scouring high and low for found elements, these artists let nothing interfere with their insight. Their exhibit is a riot of colors, crafts, and handicrafts joyfully mashed together to subvert the notion of fine art.

Beulah, Mich.-based Dewey Blocksma takes the most liberties with his mixed-media assemblage. His 11 contributions to the display are the most politically charged. With titles such as “Obama Clock,” “Robo Signer,” “Liberty Mother and Child,” and “Adam and Eve Commute,” Blocksma’s wry mixed-medias are as socially pointed as they are artistically ironic.

Like much socially conscious art, the more abstract the connection, the more lively the result. Blocksma’s “Amarillo” is a perfect example of neo-Dada walking the fine line between political inference and hermetic artlessness.

“Amarillo” consists of a metal bowl face with a strainer nose with smashed toy vehicles sticking out about its forehead. This found portrait sits on a series of colorful wooden sticks braced on 5 piles of interlaced miniature metal cars. What it adds up to is anyone’s guess, but the mash-up of “Amarillo’s” found objects crafts a symbolic bust whose incongruous parts seem to comment on the future of automotive transportation.

“Buy a Scrap of my Childhood, 10 Cents” by Len Cowgill

Among the other 20 Cowgill objects on display are 7 “Family Series” black and white photographs that have been touched up with colored pencil, white charcoal, and ink. Like many 19th century photographs, there is an arch visual quality to “Charles Galt” that’s not found in the far more naturalistic photographic portraits of today. The young Galt sits stiffly for the photographer wearing an oversized coat with wide lapels; but this is also the extent of the found image, because Cowgill then abets the portrait with alterations that range from the pallor of the boy’s flesh to two bright blue stars painted on his cheeks.

Finally, Detroit’s Tim Burke adds a touch of the Motor City’s famed Heidelberg Project to the proceedings. A longtime proponent of art brut, Burke’s contributions to this display (like his work at the Heidelberg Project’s Industrial Gallery) contain no overt self-reference. Rather, Burke’s approach is to create with an infectious abandon.

Burke’s 22 works of art range from neo-Dada sculpture to totem poles. They are whimsical admixtures—like the best of the Heidelberg Project, the world’s largest art brut project——outsider art of a stunning vitality.

“Krazy Kats” by Tim Burke

On the other hand, Burke’s “Krazy Kat” acrylic portrait of one of these cats is a relatively compact size (3 by 2 feet) with as much seemingly naïve artistic integrity as the totems. But Burke subtly shows his talent as an artist in painting a surprisingly faithful portrait of his imaginative creature. Indeed, the painting is handled in such a clever manner; it’s exceedingly accomplished art masquerading as art brut.

But even if these works weren’t illustrious enough, five of Burke’s other mixed-media sculptures carry his work one step further. His “Shaman’s Masks” portraits are made from found objects drawn from demolished churches and civic centers with human teeth added from a dentist’s collection, and found piano keys for noses.

As much assemblage and art brut as outsider mixed-media is ever going to get, these remarkable “Shaman’s Masks” are most certainly art that’s had everything tossed in—except, of course, for the proverbial kitchen sink.

“Everything and the Kitchen Sink: Michigan Outsider Art” will continue through Aug. 27 at the Ann Arbor Art Center, 117 W. Liberty St. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday-Friday; 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturday; and noon-5:30 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 734-994-8004.