African art and language exhibition in Ann Arbor

By Kwadwo Gyan-Apenteng

"Xiboli"

It is undoubtedly true that Ann Arbor is a city where art resonates with its people. The passion for art is evident in the festivals and general attitude of the people towards it in their daily activities.

Thus when an international artist storms Ann Arbor, he comes prepared especially to meet the high standards and expectations of Ann Arbor art lovers.

Ida Abreu, Cape Verdean artist and sculptor stunned patrons and art enthusiasts when his art exhibition opened at the Palmer Commons in Ann Arbor. Many art lovers and students thronged Palmer Commons to witness the electrifying event organized by the Department of Linguistics and the Center for African American Studies. (The exhibit has now closed.)

The Center for World Performance Studies funded the exhibition through a grant awarded to Dr. Marlyse Baptista, an Associate Professor at the University of Michigan, Linguistics Department and Center for African American Studies.

The purpose of the grant was to promote collaboration between the Linguistics Department and Centre for African American Studies and an artist of their choice. Marlyse Baptista showcased Ida Abreu’s work in An Arbor owing to the fact that Ida’s work is distinct, original and also in line with her study of language and art.

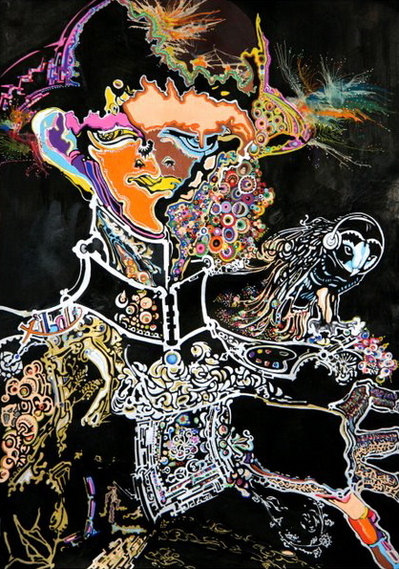

Ida exhibited 36 paintings. His pieces are unequivocally very lively and exquisite, unique and colorfully depicting diverse themes and concepts about social issues.

In one of the pieces he illustrated an ancient Cape Verdean myth about a woman who is feared as a ghost; he explained that the woman was feared and people always wondered if she was real. That piece brought nostalgic feeling to an art enthusiast who shared his experience about the African folkloric legend and how real the painting was.

Another captivating piece was about a drunk, an old man drunk in abstract art holding a gallon. It is a bright and vivacious piece that thrilled patrons at the exhibition.

Ida Abreu’s calm debonair is a contrast to his vibrant and psychedelic paintings. Ida has a distinct approach to art. He is influenced and inspired by his native country Cape Verde and his native creole language.

Ida takes such an utterly imaginative approach to his work making the pieces so believable yet in a playful and arguably abstract style that captivates his audience wondering or speculating about the true meaning of each piece.

Before the exhibition started Ida Abreu and Marlyse Baptista addressed a symposium with the theme Language and Art at the Palmer Commons.

Ida explained to the audience using his creole background as an instance: “I use a double language by allying the language of plastic art with the emotions that I can only express in my own native language, Cape Verdean Creole. I view my art as a conduit for the transmission of visual messages that are deeply rooted in the oral language of Cape Verde islands. My work is definitely a means of communication. It conveys messages and emotions that are less direct and immediate than those that music for instance can trigger but such messages and emotions can be deciphered and discovered with a little bit of observational investment and investigation of the techniques I use.”

"Ifeo"

In an interview with Ida he stated that, “The single most important objective of my art is communication. I combine my own personal experience to my craft and communicate this way with my audience”.

Ida believes that from the start, there is always a philosophy embedded in each piece of art but his philosophy is based on my own reality. He asserted, “In Cape Verde, we do not write about philosophy but we are deep thinkers and I personally always link every piece I create to my own personal experience, to the thoughts of the moment, to music or the imaginary”.

He further stated that “My personal politics definitely influence my work and given that I grew up in Cape Verde in the post-independence period when I had many exchanges with the radical youth that were active back then in Cuba and Russia, this experience created a certain dynamism and a sense of engagement that still run through my work. I am political in the sense that I am not a partisan to a particular political party but I sense that my mission is to describe what happens in my society even if this can be viewed by some as an act of civil disobedience.”

His work does not enter the frame of a particular social philosophy but each piece he creates is meant to represent instead a fixed moment, thought or image by giving them some space through which they can be imagined.

“The social and every- day-life I experienced in Cape Verde for 20 years keeps running through my work”.

Ida passionately asserts that there must be efforts to protect ancient African art and also find ways of allowing contemporary artists to circulate their art so that copyright laws will protect artists following international standards.

“It is not right that African art stays abroad and does not go back to Africa. We must do this for the African Youth so that they know there is an infrastructure in place that protects them and benefits them. It is a very difficult job to be an artist, so young artists must be at least provided with the reassurance that their art will be protected and safeguarded by copyright laws. The same must be done for ancient African art; it must be protected and restituted to Africa for those pieces that are still abroad. If we wish for our culture to thrive and to benefit society and individuals, we need to create a market that defends and protects artists.”

In a related interview, Marlyse Baptista was optimistic about the impact of the exhibition. She observed, “The impact of this project can be felt to this day in the way that Ida’s works touched the audience who came to see the exhibit. The aesthetics, power and meaningfulness of every piece left no one indifferent and isn’t that one of the objectives of art? Allow viewers to access and experience a higher realm of meaning and beauty.” She said, “The portraits that Ida exhibited in Ann Arbor seemed to have a life of their own. They were like living and breathing characters to me rather than mere paintings”.

From the age of 12, Idá Abreu exchanged his toys for sculpture and drawing, which he practiced daily with no formal training nor teacher, using whatever tools he could find. He grew up in Achada Santo António, a populous neighborhood in Praia (Cape Verde islands) where he witnessed life’s challenges, as well as the inner wealth and beauty of humble people. This insular environment fed and bolstered his creativity and gave him a taste for multicolored backgrounds and a keen sense of detail clearly observable throughout his art works.

Self-taught, this ingenious sculptor and painter, yields to no passing fads, nor to any enticing exoticism or complacent academic trends. His works, alluring and surprising, express above all the originality of creole plastic art, at once universal and unique. Idá Abreu’s contemplative eye on his own people and the visceral rootedness to his homeland convey a rigorous, yet original esthetics.

Ida said “Artist’ is not a noun but an epithet and it should designate a state of constant evolution and not a profession”.

Ida has become an inspiration many artists in Cape Verde and also in France where he lives with his family. He continues to illuminate the world about African art, language and culture.

Kwadwo Gyan-Apenteng is a Ghanaian journalist and filmmaker now living in Ann Arbor Michigan. He has cut his teeth writing arts for several newspapers in Ghana, West Africa. Kwadwo is also an arts writer for New African magazine in the United Kingdom.