African Americans and the New Deal: Photo exhibit uncovers treasures from the archives

Government agencies in the 1930s sent out photographers to capture evidence of how the New Deal economic plan was going. During President Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration, programs like the Farm Securities Administration, Works Progress Administration, and other New Deal agencies used the photos to document their progress and for PR.

We have seen many New Deal photographs before, like Dorothea Lange's famous photos of migrant workers and people devastated by the Dust Bowl disaster. But often missing is photographs showing African Americans getting some New Deal opportunities.

Independent historian and author Rickie Solinger was researching FDR in the National Archives and the Library of Congress, when she started coming across photos of black people benefiting from education, literacy, employment, farming, housing, health-care, and arts programs, to name a few.

U-M English and women's studies professor Ruby Tapia brought the exhibit to Ann Arbor to complement the UM School of LS&A's theme this semester, "Understanding Race." It is one of several exhibitions around campus on the theme.

The first three photographs you see, on the right wall of the entrance way, are by famous New Deal photographers Dorothea Lange and Jack Delano. These three introduce us to the different generations of people who lived in the 1930's.

The older couple in Lange's portrait lived through slavery, and the photograph reminds us of that past. Next to it, a shadowy family portrait of Ella Patterson and her grandson at the Ida B. Wells Housing Project in Chicago shows generational transition in the 1930s present, taken by Delano. Another photo by Delano hangs next to that. A young teenage girl leads a discussion with other young people around a boardroom table at the same housing project. Her generation will help shape the civil rights movement in coming decades.

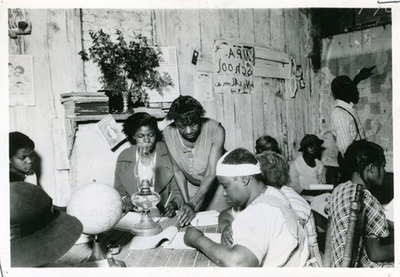

Most of the photographs are grouped to show the different kinds of opportunities African Americans had during the New Deal era. A group of students attend a literacy class, a man learns how to vote, a farmer handles his loan, black men and women obtain employment—these are a few major themes in the exhibition.

At its heart, the exhibit illustrates "how African Americans took opportunities opened up by government programs in the 1930s to claim their status as dignified persons and citizens, in some respects laying foundations for the Civil Rights Movement," in the words of the exhibit statement.

Pointing to one of the photos, the senior public relations representative for the Institute for Research on Women & Gender told AnnArbor.com about the importance of literacy to African Americans in the 1930s. "We take it for granted, but learning to read and write has to do with citizenship. It is a right of citizenship to be able to read a ballot and vote. It is a natural right in this country that had been denied to many African Americans," Debra Schwartz says. The image shows a group of black women of all ages attending a literacy class.

But before you take all of these photos as fact, it is best to pause and think critically. How much do they tell us about the actual lives and fates of these individuals? And how much do they reveal about what FDR's government had to say about itself during the New Deal?

Schwartz definitely thinks there is a spin here. "That spin is that African American culture is coming up," she says. It is a very optimist message about economic and racial progress that comes through in these photographs. So therefore, "you definitely have to remember that they are PR photos," she says.

There is a limit to how much we can know about the fate of each individual. As much as the photos speak about people claiming their rights as citizens and aspiring to something greater for themselves, it might be an overly optimistic portrait of the African American experience of the New Deal. We do not know if that man ever voted again. Did the farming assistance help this particular man fulfill his dreams? We can only hope in those cases.

The people in Lane Hall think a lot about the "intersectionality between race, class, and gender," Schwartz says. The building is home to the Department of Women's Studies and the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, which are two of the exhibition's many sponsors across the university.

One intersection between gender and race, which Schwartz and other exhibition organizers noticed, is that men and women are almost always photographed separately. "What I think the curator wants to argue here is that, if you walk around the exhibit, you notice there are many photos of men and many photos of women. However, they don't generally seem to be operating in the same spaces," she points out.

Schwartz thinks this reveals how "they were given out opportunities that were gendered opportunities. For example, you put the women into clerical jobs, while you let the men work the stream rollers," she says.

The photographs are significant because they add a piece to the puzzle of American history by uncovering more details about black history. They are challenging because they require a critical eye. The exhibition is well worth a look before it closes this Friday and moves on to New York.

The exhibit is open to the public during university business hours. Admission is free. Lane Hall is located at 204 S. State St. Phone 734-764-9537.