University of Michigan architecture school opens state of the art digital fabrication lab

The University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning has unveiled a digital fabrication lab - called the FAB lab - that its creators say will help close an existing gap between design and manufacturing in architecture.

By providing students with the means to work with building materials on a larger scale and with more precision than most academic labs, Wes McGee, the FAB lab director, said students become more familiar with materials than they would at all but a handful of schools worldwide.

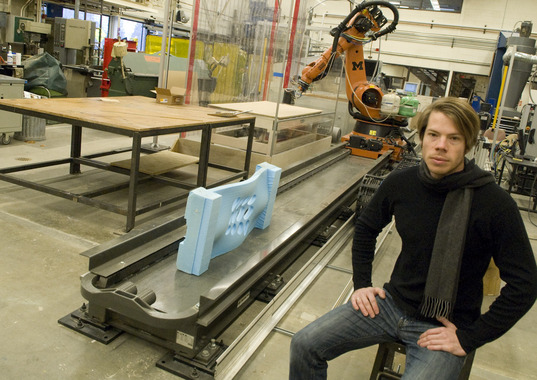

Wes McGee, director of the FAB lab, says it will help close an existing gap between design and manufacturing in architecture.

Tom Perkins for AnnArbor.com

“Now that they can actually produce the parts they draw, they run into the problems that they wouldn’t otherwise, and it kind of creates kind of a feedback loop between design and fabrication,” he said. “I think that feedback loop is what we try to push as being on the cutting edge of education for design.”

The centerpiece of the FAB lab is a seven-axis robot with a 30-by-10-by-8-foot work envelope, which is the area in which the robotic arm can operate.

The arm uses several methods for cutting materials. Milling heads cut wood and foam, while a water-jet head can carve out harder materials like steel, stone or glass. The water shoots out of the jet head at 60,000 pounds per square inch, moves at three times the speed of sound and can cut through 1-inch of steel.

Because the water is shooting straight through the material, it has the ability to follow compound-curved surfaces and cuts with minimal lateral forces, simplifying how a material is fixed in place.

McGee said it's especially useful when cutting three-dimensional shapes.

Water jet-cut steel that has been folded.

Tom Perkins for AnnArbor.com

“Once you start cutting 3-D shapes, designing how to hold the part is almost as complicated as designing the part itself,” he said.

In addition to the robot, which was functional this past September, the FAB Lab also offers students computer-numerical controlled (CNC) machines, a three-axis abrasive water jet cutter, a three-axis milling machine for 3-D cutting and rapid prototyping machines.

Karl Daubmann, a professor at the Taubman College of Architecture and partner at Ply Architecture, has been pushing for the school to obtain this type of technology, which he sees as important in the future of the field. One of Ply’s more recent projects was creating a custom ceiling structure comprised of a series of aluminum pieces for Ayaka, a small Ann Arbor sushi restaurant.

Using technology and processes students at U-M will now have access to, Ply designed and cut the aluminum pieces, then worked with a contractor who bent and installed them.

Daubmann believes the students' experience in fabrication will improve the architect-contractor relationship, and he thinks more knowledge on the side of the designer will drive down the price of custom work and reduce waste.

“Architects don’t build things, so to start to give them a chance to play with these materials - the hope is for them to be better collaborators,” he said. “We’re not looking to replace contractors, but it’s a way for us to interact with them in a more meaningful way.”

McGee agreed workflow efficiencies emerge when architects better understand their materials.

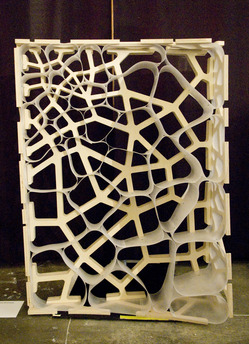

CNC water jet routed plywood and polypropylene plastic.

Tom Perkins for AnnArbor.com

“Certainly on the design side there’s an interest in the fabrication, and with the architect understanding the fabrication process, they can now embed that knowledge into their design,” he said.

McGee said the FAB lab is one of the few places where budding architects can learn the materials and the fabrication process that has made firms like Ply successful.

“The way something turns out is not always what they intended, but maybe it’s because they didn’t understand what it takes to build those parts,” he said. “The drawback to working on a computer is there’s not a lot of materiality in the computer, so they don’t get to see how a material behaves.”

McGee said many schools still believe in the old divisions between the contractor and designer, but U-M's architecture school, which is one of the larger in country at 400, is moving in a different direction philosophically.

The FAB lab is a result of that movement and was a product of the combined efforts of McGee, Daubmann and Monica Ponce de Leon, dean of the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning and a partner at Office dA. All three previously or currently work for firms that employ methods taught in the FAB lab.

“There are a lot of people here that are interested in blurring those old boundaries and getting their hands dirty with the processes,” McGee said.

Tom Perkins is a freelance reporter for AnnArbor.com.